Bernard Seeber was a man of genuine brilliance, in full possession of incredible mental agility and clarity. Fierce, strict and principled, he worked systematically, always with an ordered logic, a love of assembly, and the careful placement of selected parts. He wanted his buildings to tell a story, to make efficient use of materials and space, and to integrate holistically with their landscape. As a result, they are as direct, optimistic and generous as their author.

Close colleagues describe Seeber as “incandescent.” Between grief and laughter, they speak of a man whose energy and determination to deliver a project challenged and pushed those who worked with him. “Hold the line” was his way of maintaining a path toward the successful delivery of a project.

Seeber eschewed the singular author-architect paradigm. Read any project description and you will find his name placed last; he encouraged his team to be seen and heard, and to be acknowledged within the public realm.

The Fremantle Cemetery Chapels Crematorium Complex (1997) by Bernard Seeber, winner of the George Temple Poole Award in 1997.

Image: Marion Treasure

After working in Melbourne and London, Seeber returned to his hometown of Perth in 1979, and started working for John Duncan at the respected modernist practice Duncan Stephen and Mercer. Duncan was an architect and structural engineer with a blunt, pragmatic and fundamental point of view. This aligned with Seeber’s principles and provided a rich training ground.

Seeber left Duncan Stephen and Mercer in 1983, upon the completion of conservation works to Trinity Arcade, to establish a practice in Fremantle. One can see the long strands of knowledge he received and then wove through the office at 152 High Street and into the work of significant younger architects. May these strands continue – but please, let us also preserve their source and tell their stories, to maintain the origins of this received wisdom.

Forever generous with his time, Seeber took any opportunity to speak with students of architecture and fellow architects, conveying the careful rationale of his working, his buildings and his sense of civic concern. He was bursting with energy and his optimism was infectious. His wit and humour are broadly remembered, as is his capacity to be provocative – sometimes outrageously so, as is clear from his time as the editor of the West Australian chapter of the Australian Institute of Architects’ official publication, The Architect (1984–1987).

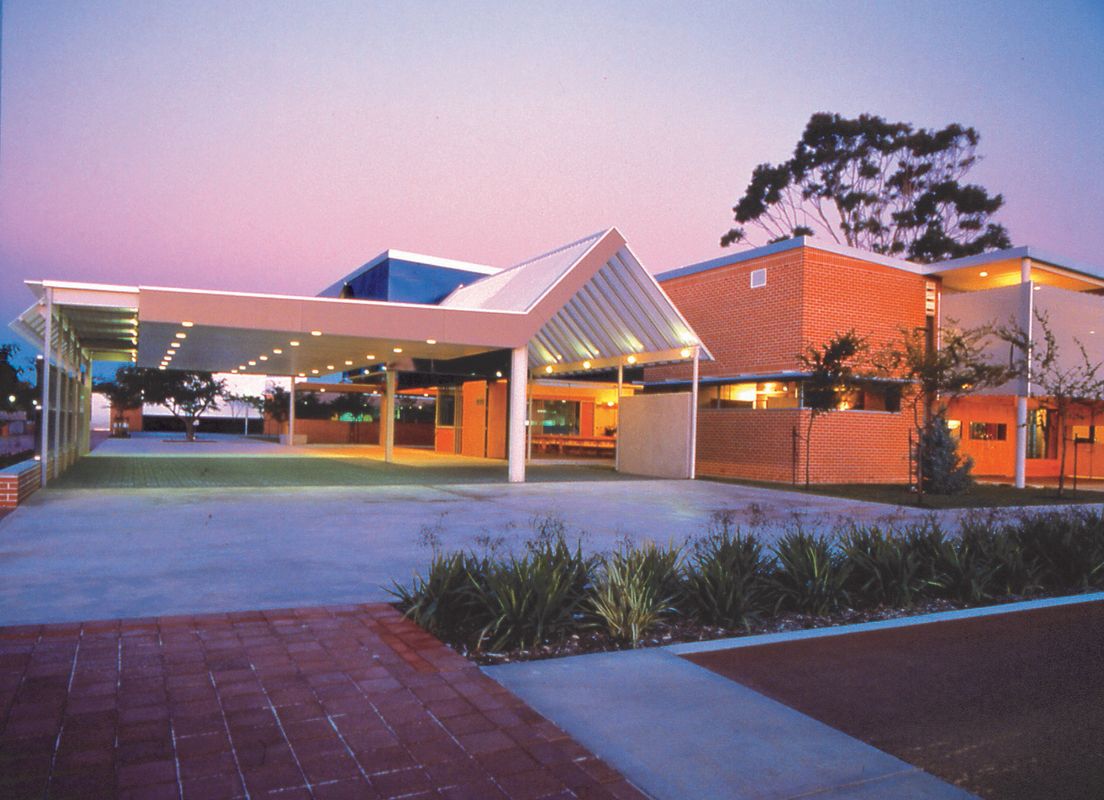

Hilton Community Centre (2011) by Bernard Seeber, winner of the George Temple Poole Award in 2012.

Image: Angus Martin

Fostering egalitarian tendencies, and having established frugality as a virtue, Seeber applied his architectural intelligence and rigour to many small-scale, low-budget projects. For him, all projects were equally deserving of this discipline. His lifelong interest was in community and affordable housing.

Seeber’s fascination with human behavior, patterns of social relationships and aspects of culture associated with everyday life helped him to craft spaces within buildings and the environments in which they sit. Where Seeber stopped and his buildings began it is impossible to say because he worked within a worldview that was whole and all-encompassing. His inquisitiveness led to alternative concepts in which spaces could be derived, based on his conviction that an architect’s central responsibility is to the common good of all people, without discrimination.

The Fremantle Cemetery Chapels Crematorium Complex (1997) is an example of this conviction. In the Winter 1997 issue of The Architect , the journal of the Western Australian chapter of the Australian Institute of Architects, the writer and critic Irving Schwartz described the work: “People are given the opportunity to witness the coffin at the furnace – an important aspect of Hindu and Buddhist committals … Spaces are ‘open’ to interpretation, thereby accommodating the variety in our culture make-up … The facilities are light, open and spiritual, if you like, and non-mystical.”

Leighton Beach Facilities and Kiosk (2016) by Bernard Seeber.

Image: Douglas Mark Black

Some of the many highlights of Seeber’s built works are the City of Fremantle Leisure Centre Facilities (2002); the Kerman Office Building (2003); Margaret Street House (2008); Hilton Community Centre (2011); Fremantle Railway Station restoration (2011); Stockdale Road Residential Community 2012); Cottesloe Cancer Wellness Centre (2014); Kadampa Meditation Centre (2014); Leighton Beach Facilities and Kiosk (2016); and South Street Housing Community (2019).

Seeber won the George Temple Poole Award at the Australian Institute of Architects’ West Australian chapter awards twice: for the Chapels Crematorium Complex in 1997 and for the Hilton Community Centre in 2012. Few architects can claim such high levels of consistency throughout the life of their practice.

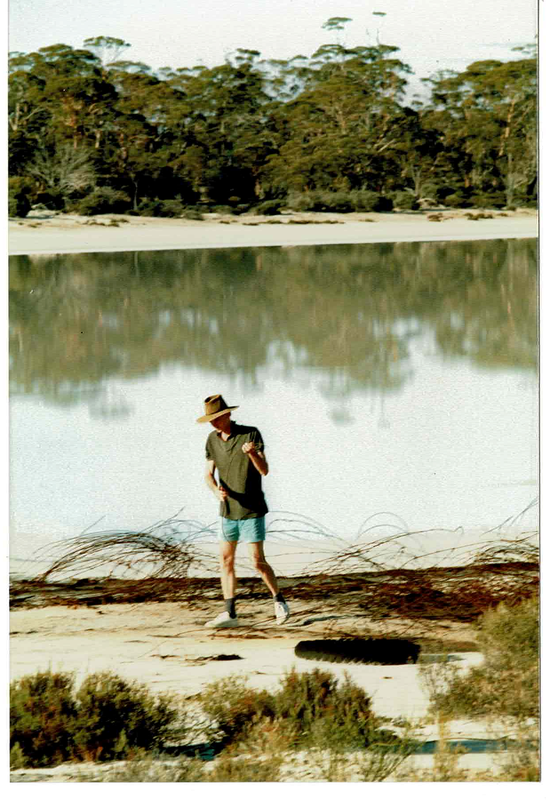

His colleagues recall Seeber’s love for the Australian landscape – in particular, salt lakes, in which both the man and his architecture would breathe and rest easy. Finally, it must be acknowledged that a select group of our profession, who worked closely with Seeber in Fremantle, saw him as a mentor. To untold others, however, he was a role model for how one might conduct oneself intellectually, professionally and personally. The respect of his peers is to be one of his numerous and enduring legacies.