gathay nyiirun yanyi, gathay nyiirun ngarray, barrayga, nyiirun ngarrayn ngarralgu

Together we all will walk, together we all will listen, on Country, we all think towards knowledge (remember)

The following relies on my own lived experience as a Worimi and Biripi Guri (man), my own connectedness to Country and position within a broader First Nations cultural framework, and interpretation of shared knowledges, story and practice.

Ngaya (Mother): creator, architect, urban designer of barray (Country), sculptor of landscape since time immemorial informing complex ecosystems so that all beings and elements can coexist. This is design as intended and understood by First Nations cultures and reciprocity with Country. It is songlines and story expressing the ancient infrastructure embedded in the eroding sand-trails leading from the mountain ranges to the oceans, through the veins of the river system nourishing the Red Centre, to wind and time as they pollinate the evolution of these intertwined systems, which exist one because of the other.

Reciprocity is one of many principles that drive the interconnectedness of Country – spiritual, tangible, and intangible. An understanding of the equilibrium of existence and the network of reciprocal relationships between all elements and beings is fundamental to unlocking narratives of place. Connecting and designing with Country requires meaningful engagement with First Nations systems of being, knowing and practising. As we are learning to embrace the lessons embedded within our landscapes, the built environment is awakening and realizing the rich relationships, stories and ways of First Nations cultures.

My confidence in the future of the relationships between our young cities and this living, ancient land comes from the enthusiasm I see, the tough but constructive conversations occurring, the evident eagerness to learn, and the rising representation of Mob in the design sector. This is an exciting era and the beginning of what I envision to be a healing of landscapes.

We have a long journey ahead, including many truthful yarns, on our way to collectively advocating for Country. For millennia, the colonial machine has evolved, finding new and inventive ways to commodify land, culture and people – resulting in the physical manifestation of the built environment. The earliest manifestation commenced with Arthur Phillip and the First Fleet.

“The beginnings of any colonial enterprise are proverbially insensitive to local cultures, so why should we be surprised that Phillip ignored, or chose to ignore, the very definite indications of an existing urban structure?” 1

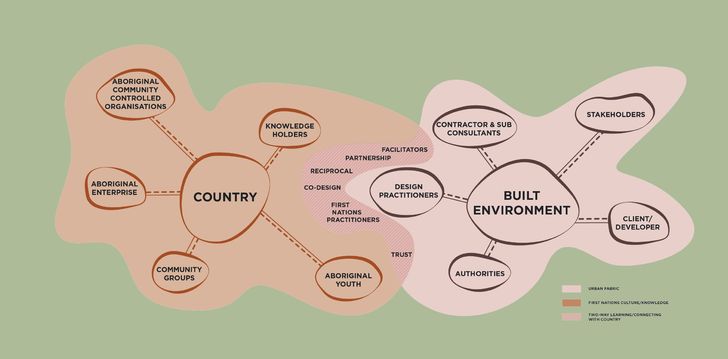

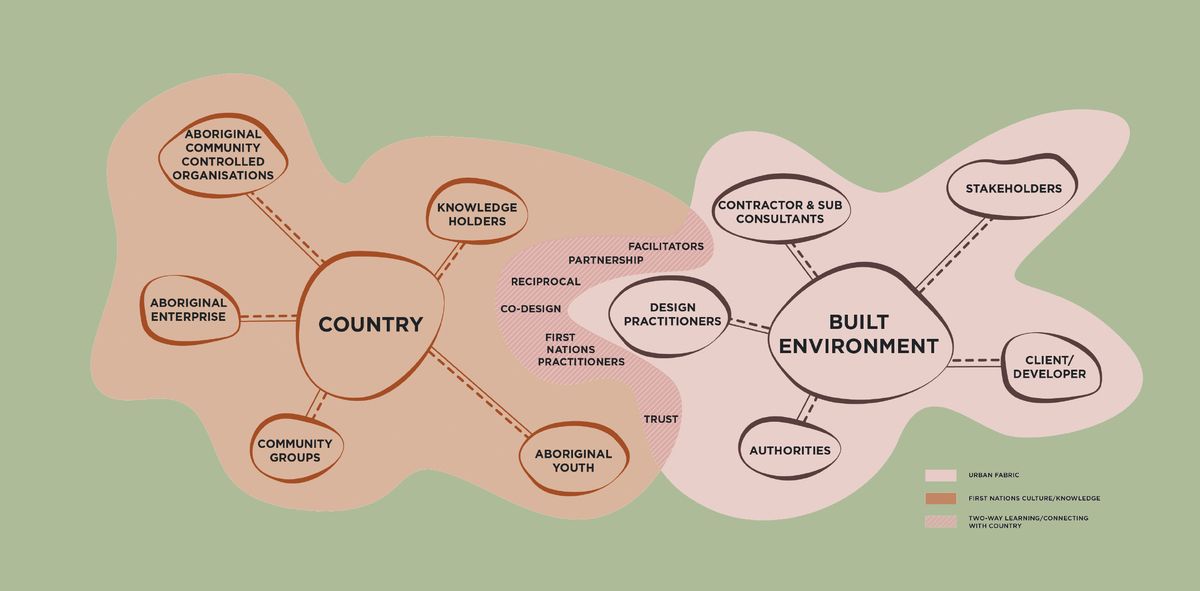

To unlock the narratives of place, we need to understand the network of reciprocal relationships between all elements and beings, and the intersection of cultural knowledge systems and the urban fabric.

Image: Jack Gillmer

Country has endured this construct for more than 250 years and the colonial enterprise has made Mob cynical; we hesitate when faced with developers and designers looking to connect with Country in the form of a one-way, extractive relationship. At a foundational level, policies such as the Aborigines Protection Act 1909 have historically excluded First Nations communities from important conversations. Only recently has the opportunity arisen for First Nations voices and collaborations to “Indigenize” the built environment. The potential is great, as there already exists an urban infrastructure developed since the beginning of time with this ancient cultural landscape.

Engagement with First Nations cultures – and therefore Country – requires trust, generosity of spirit and a genuine desire to build relationships of reciprocity over time. It requires personal investment and a commitment to co-design from the beginning, across all phases of development. Through an embedded collaboration of continuing connections, use and participation, shared visions of the future can develop. Active engagement may be difficult without existing relationships, a familiar face, or proven capability of advocacy and opportunity. As the architectural profession navigates this space, we need to understand that each project is an iteration of a process undergoing change. Each successful project will support the next to enact shared responsibilities so that everyone and everything can better connect with Country.

Connecting with Country in the urban fabric is not a trend, but a movement established through decades of lobbying and initiative by a handful of influential and trailblazing First Nations design practitioners. Now, we are revolutionizing the way we practise architecture, developing briefs in response to Country and the colonial paradigm, where the latter has resulted in the destruction and dispossession of unceded land. This revolution will enable future urban design strategies to celebrate and heal landscapes.

The Government Architect New South Wales’s Connecting with Country framework (2023) 2 is a valuable tool in instigating interactions between First Nations cultural practices and the built environment. It has established a methodology for agency for communities and their future aspirations in this realm. Connecting with Country is more than an aesthetic response added to a project; it is about the communication and the relationships between the social, the physical and the spiritual. Deep knowledge of Country requires an innate affinity with Country, which in turn relies on relationships with Aboriginal people who are keepers of this knowledge. The co-design process involves an exploration of the intersection of cultural knowledge systems and the urban fabric.

To help clients, project teams and stakeholders genuinely connect with Country, and to ensure the safety of culture in the built environment, we need to avoid cultural appropriation of shared story for short-term gain. There are obligations for everyone to improve their cultural capacity and literacy, to foster curiosity and to be patient in the face of truth-telling. To find richness, the process must be deeply committed to connecting with Country, and respecting community engagement as a fundamental principle of Indigenous design. 3

Together, we can comprehend the critical nuances of connecting with Country in the built environment, reflect on collaborations to date, and establish roles in architecture and urban design that are innovative and new. 4 We face an exciting and daunting proposition: co-creating a uniquely Australian vernacular in partnership with Country and First Nations communities. Some will lean toward what they know; the brave will extend their arms and embrace the vast ecologies of Country.

The intersection of cultural knowledge systems and architecture is a space of unrealized opportunity and endless potential. I ponder what our cities would look, feel, smell and sound like if we designed with the knowledges of the rich culture of this land. I wonder how an urban strategy flowing with songlines would connect us all as part of Country, and what might be expressed in the sculptural masses of a unique response to story. Would our relationship with other beings be different? Would they still bounce, slither, glide or waddle away from our cities? Below the concrete blanket of our urban fabric lies a latent landscape of rich, living knowledge just waiting to be respectfully celebrated.

I encourage people to venture on their own journey of discovery to connection with Country. Listen to the rustling leaves of the eucalypts, question your navigation through the landscape and its relationship with the elements, all beings, memories of place and future aspirations. It is up to all of us to connect with Country. It is up to all of us to reshape the ways we practise architecture. It’s time that we embraced, celebrated, listened to and walked with Country, for together we can create a better future.

wanyimbuwanyimbu ganyila, wanyimbuwanyimbu ganyiy

Always was, always will be

Thank you to Kaylie Salvatori, Leroy Maher, Michael Mossman and Monica Edwards for their generous feedback and support.

- Peter Myers, “The Third City: Sydney’s original monuments and a possible new metropolis,” Architecture Australia , vol. 89 no. 1, Jan/Feb 2000, 80–85.

- New South Wales Government, Connecting with Country (Sydney: Government Architect New South Wales, 2023); governmentarchitect.nsw.gov.au/projects/designing-with-country.

- Alison Page and Paul Memmott, Design: Building on Country (Melbourne: Thames and Hudson Australia, 2021).

- Brook Garru Andrew et al., Galang 01 (Sydney: Powerhouse Publishing and Garru Editions, 2022).