John Andrews had an extraordinary life and career. Having completed a bachelor of architecture at the University of Sydney in 1956, and after a stint at Edwards, Madigan and Torzillo, he undertook a master of architecture degree at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design under José Luis Sert and Sigfried Giedion. In 1958, with three of his fellow MArch students, Andrews entered the Toronto City Hall and Square design competition, an event as internationally famous as the Sydney Opera House competition of the year before. Andrews and his colleagues came second. This success changed his life professionally and personally; it gave him the confidence (and some cash) to ask Rosemary Randall (“Ro”) to marry him. The two had met shortly before he left Sydney. The wedding was at Cape Cod.

The City Hall competition led to a job offer with the ambitious Toronto firm of John B. Parkin Associates. There, Andrews honed his skills of designing for climate – skills he had precociously demonstrated in his City Hall proposal. He also contributed to the structural resolution of the winning City Hall design by Finnish architect Viljo Revell, who worked with Parkin to realize his project.

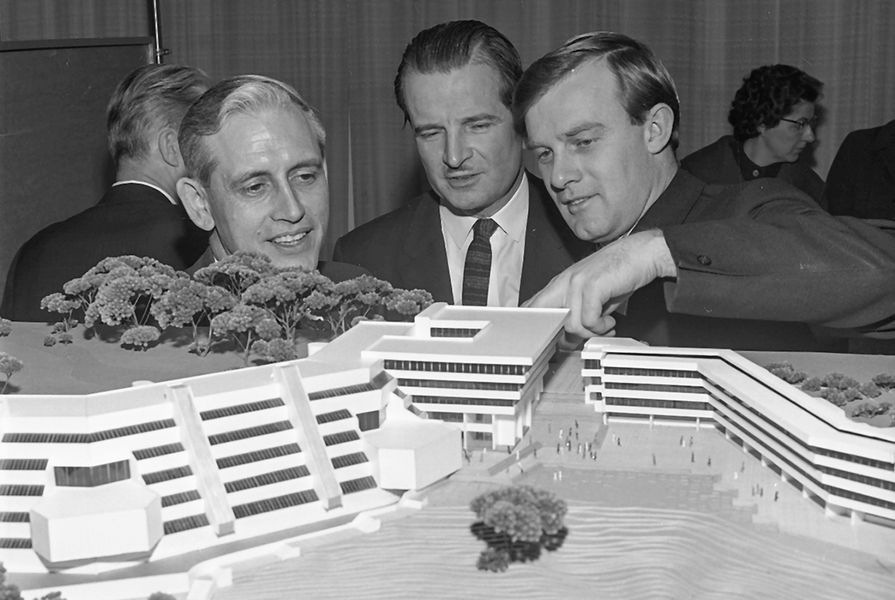

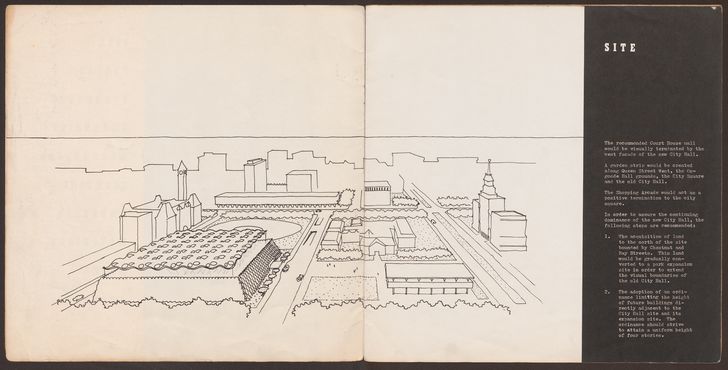

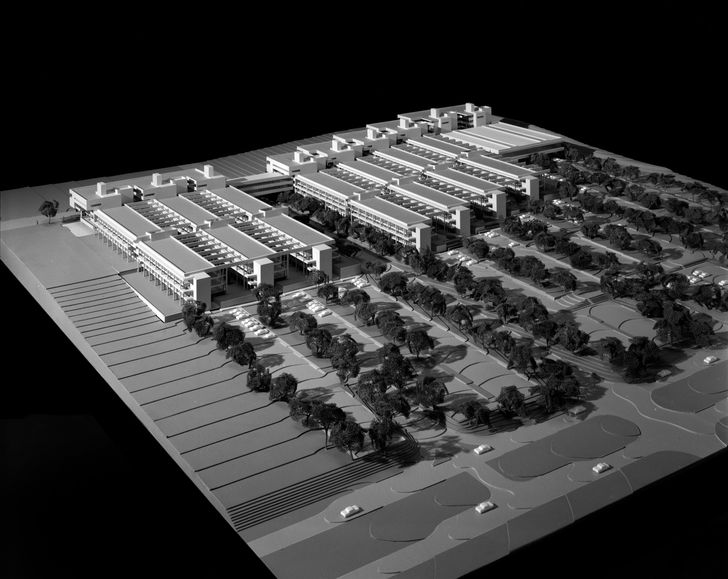

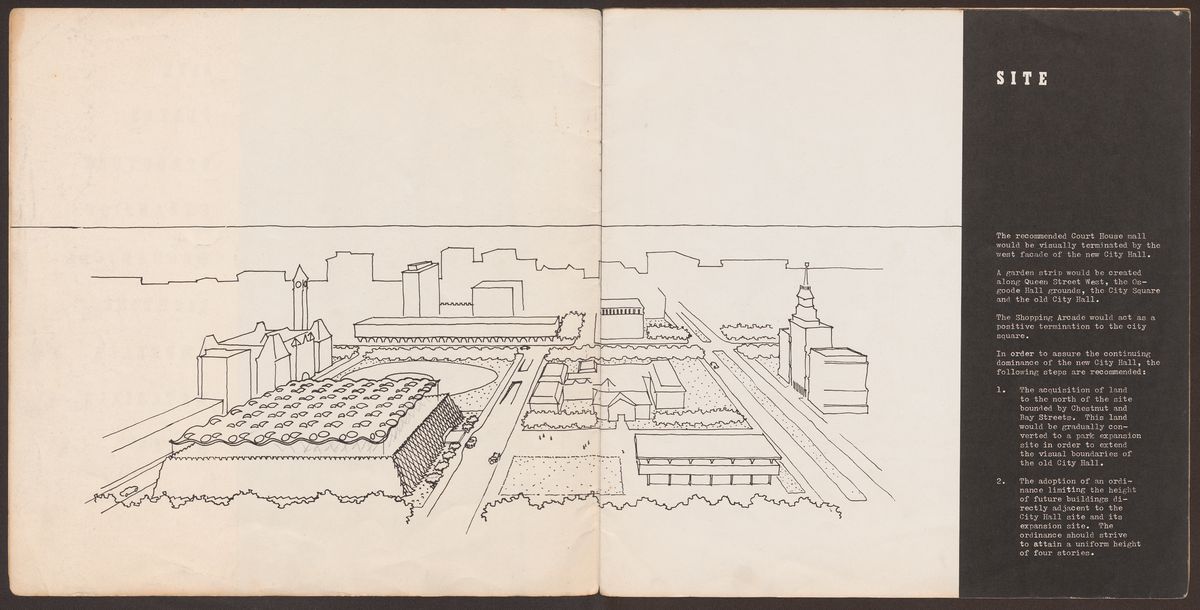

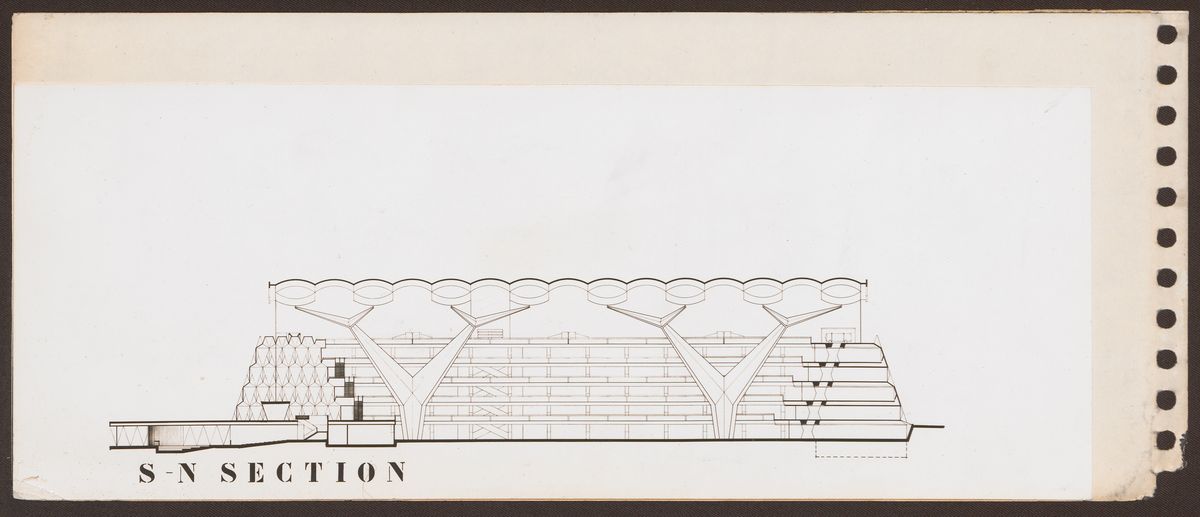

Site perspective of John Andrews, Macy Dubois, Bill Morgan, and Bill Ireland’s entry to the second stage of the Toronto City Hall competition, 1958.

Image: John Andrews and team

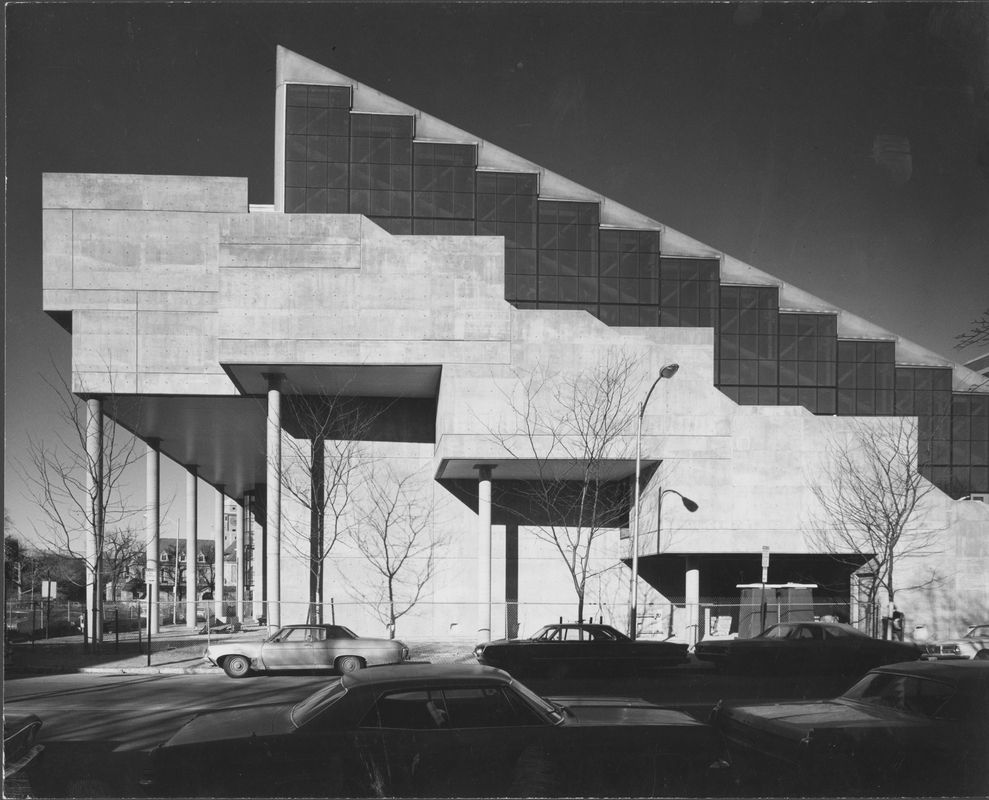

In 1961, Andrews left Parkin to tour Europe, the Middle East and India, particularly visiting the post-war work of Le Corbusier, including the under-construction buildings at Chandigarh. After a brief interlude back in Sydney working with Peter Stephenson of Stephenson and Turner, he returned to Toronto, where he started teaching at the University of Toronto’s school of architecture. In 1962, he was appointed with two colleagues – planner Michael Hugo-Brunt and landscape architect Michael Hough – to conceive a plan for a new satellite campus of the university at Scarborough in Toronto’s eastern suburbs. The architectural commission followed. Andrews devised a single building to house 5,000 students in arts and sciences in an inflected linear form, with an internal “street” following the top of a wooded ravine. A bravura composition in off-form concrete, it exemplified the megastructural moment of the mid-1960s and, when it was opened in 1965, it won international plaudits. Andrews was made professor and chair of architecture as a result. While he promoted important reforms in the architectural curriculum at Toronto, he was set on developing an architectural practice rather than an academic career.

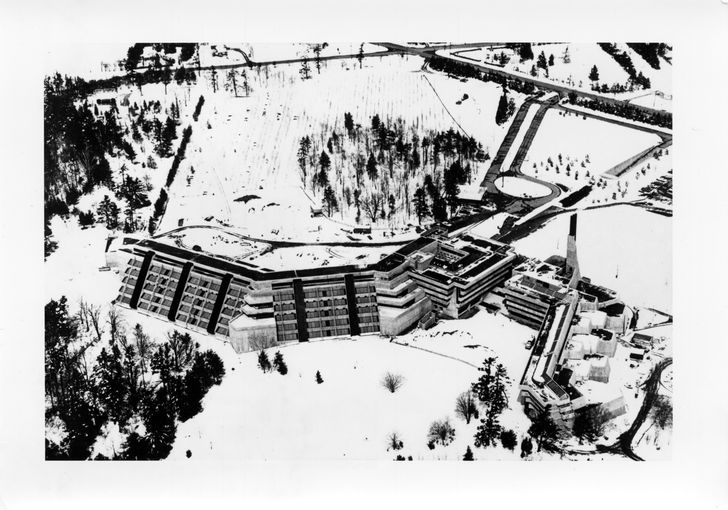

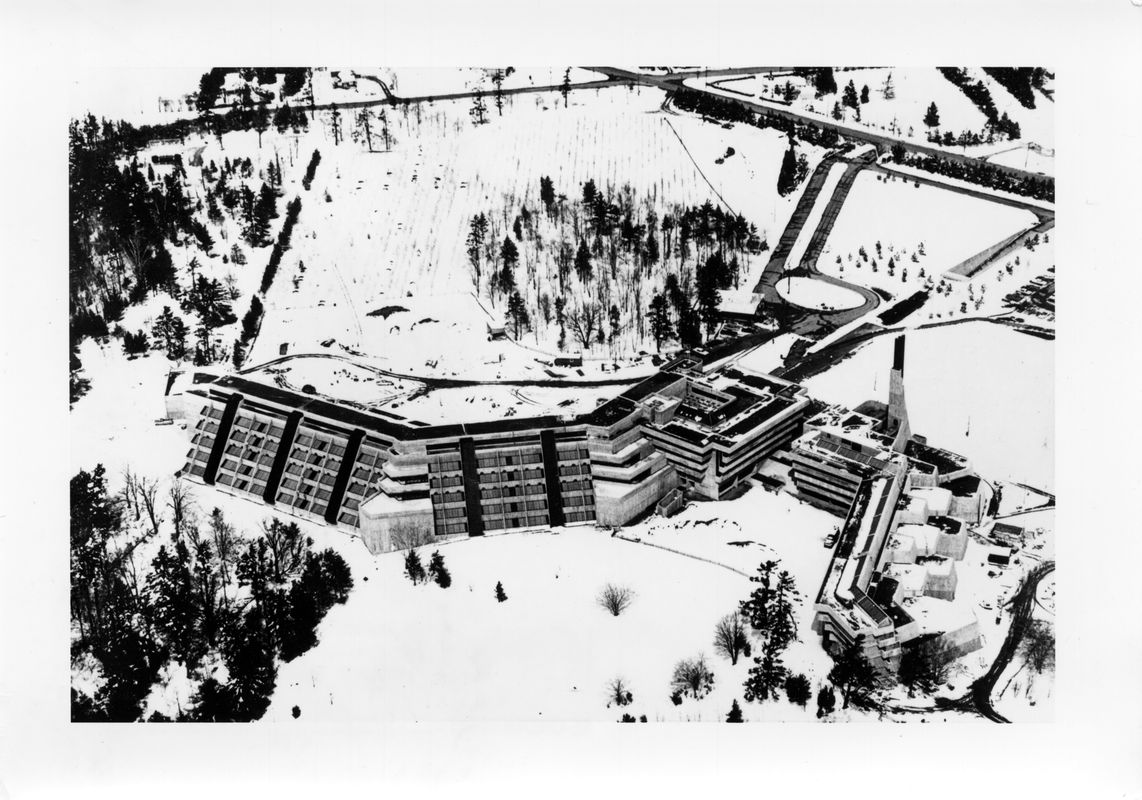

Scarborough College. Photo by PANDA, Canadian Architecture Archives, University of Calgary

Image: PANDA

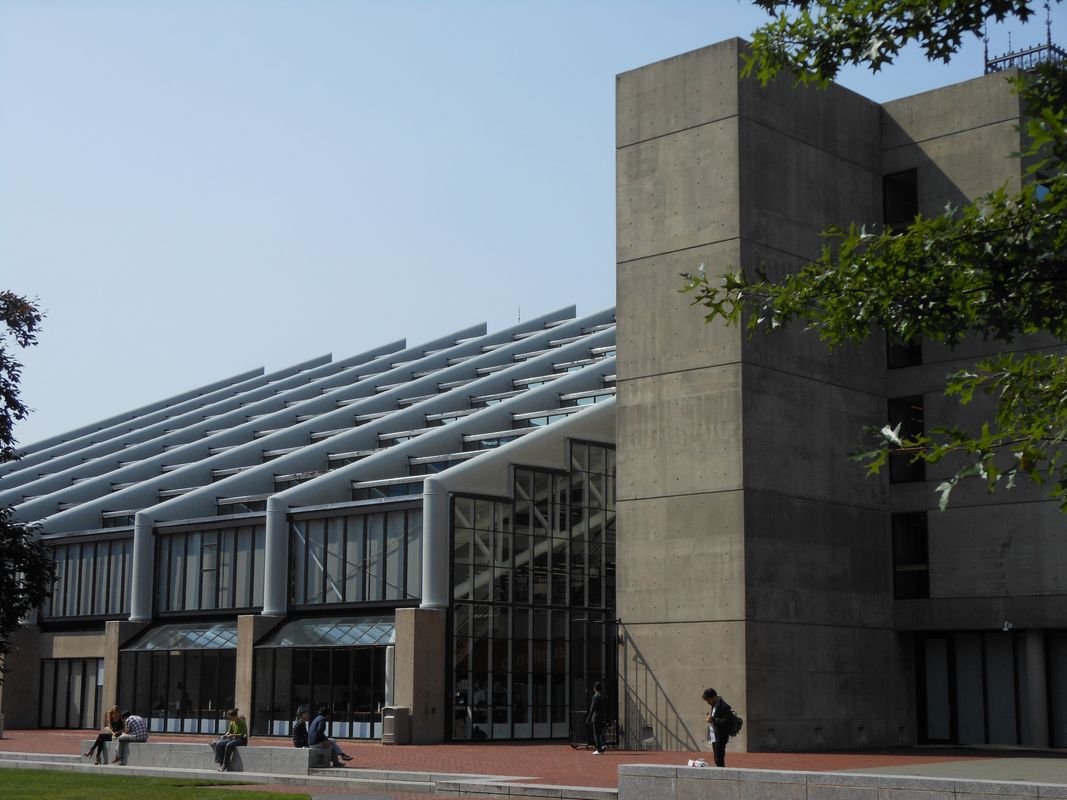

Scarborough’s success led to many other university commissions in Canada and the United States, including the South Residence at the University of Guelph (reputedly the largest student accommodation project in North America) and smaller projects for prestigious American institutions such as Smith and Sarah Lawrence colleges. As he had at Scarborough, Andrews introduced an urban order in each of these projects, or further elaborated urban opportunities latent in the context. Most prestigious of all was the commission he received in 1967 (almost certainly at Sert’s instigation) to design Gund Hall, the main building of Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. The dominant canted roof form at Gund, supported by steel tube trusses glazed at their vertical faces, expressed the centrality in Andrews’ design of the studio “trays,” with all the disciplines of the school – architecture, landscape architecture, urban planning – sharing the energetic, multi-level space under this roof.

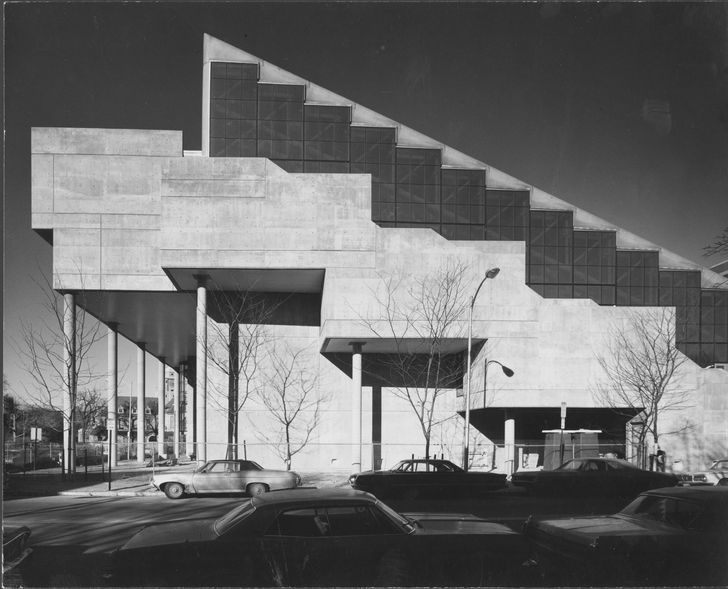

Gund Hall by John Andrews, 1968-72.

Image: Photographer unknown

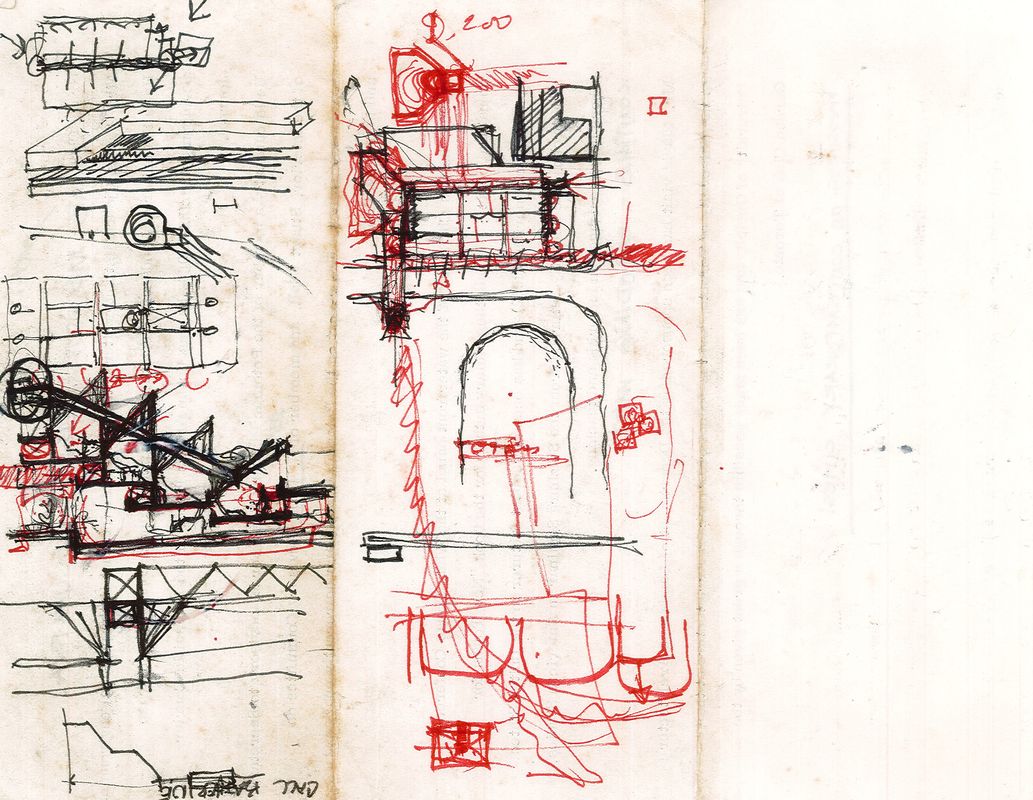

In 1968, John Overall of the National Capital Development Commission offered Andrews the design of Cameron Offices in Belconnen, a new satellite of Canberra. Seizing the opportunity to return to Australia, he relocated his family (he and Ro had four sons) from Toronto and set up an office in Palm Beach in Sydney’s north. Devised to house 4,000 federal bureaucrats, Cameron was organized as seven office wings linked by a north-south pedestrian “mall” at the eastern side. This mall was supposed to be connected to housing further to the east, and – most importantly to the logic of the scheme – a rapid transit node and a town centre to the immediate north. However, the disestablishment of the commission led to these plans being abandoned, undermining Cameron’s urban order. Reports that Cameron Offices leaked due to design faults led Andrews to sue the Sydney Morning Herald and two other newspapers for defamation. He won. But poor maintenance practices at Cameron (not the architect’s responsibility) did indeed lead to problems.

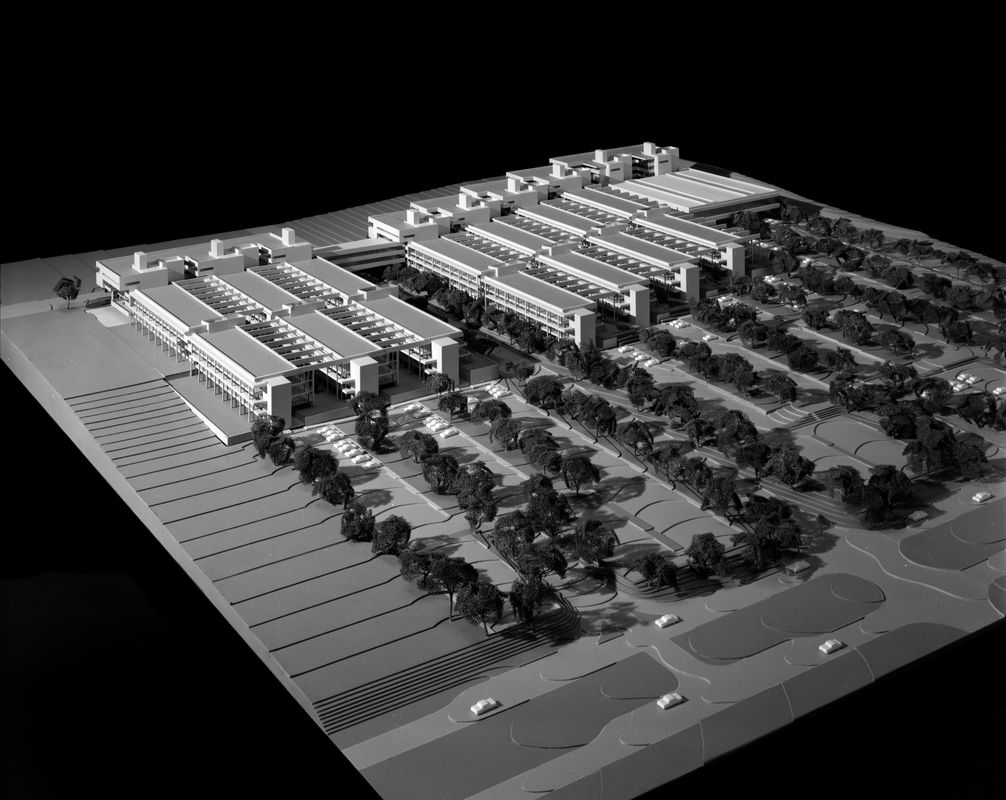

Model of Cameron Offices. Photo by PANDA, Canadian Architecture Archives, University of Calgary

Image: PANDA

In Australia, Andrews continued to undertake university projects: Toad Hall at the Australian National University and residences at the Canberra College of Advanced Education are significant examples. In the late 1970s and the 1980s, institutional projects dried up as the neoliberal ethos of “small government” took hold in Canberra, and Andrews increasingly looked to commercial projects. He had a notable success in the King George Tower in central Sydney, completed in 1976. Later office projects, such as the Octagon Offices in Parramatta, clustered octagonal floor plans with vertiginous atria between. Repeated octagons had first been proposed by Andrews for another Canberra complex, the Callam Offices at Woden, in 1973, but with the octagons widely dispersed and connected by walkways and vertical circulation nodes. Partly realized as a college of technical and further education five years later, only three of the proposed 24 octagonal pods were built. Callam, however, became the template for Andrews’ last international success, the competition-winning design for the Intelsat headquarters in Washington, completed in 1988. Nine high-tech octagonal modules of six floors each are connected by glazed, planted atria, technically calibrated to enhance the building’s environmental performance.

Sydney Convention Centre, December 2014.

Image: Peter Bennetts

Andrews won many accolades across his career, notably the Gold Medal of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects in 1980. He was made an Officer of the Order of Australia in 1981, “in recognition of service to architecture.” But Andrews had many interests other than his architectural practice. He owned a farm at Eugowra, where he built a fine, steel-framed house and raised a herd of pedigree deer. Nearby at Canowindra, he grew vines from which the highly regarded Hamilton’s Bluff wines were made. For 10 years from 1978, Andrews was involved in the Australia Council, becoming chair of its Design Arts Board. In this role, he helped to promote design’s cultural and economic significance, to exhibit Australian architecture at home and abroad, and to bring the editors of international design journals to Australia. He also championed an Australian pavilion at the Venice Biennale.

He served on the juries of two internationally significant competitions: for the new Parliament House (1979–81) – won by Mitchell/Giurgola and Thorp – and for the Hong Kong Peak Leisure Club (1982–83) – won by Zaha Hadid Architects. A late modernist Andrews might have been, but he supported talent however it manifested itself.

In the 1980s, Andrews built three convention centres in Australia, in Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney. Adelaide and Melbourne were accomplished, but the Sydney building was another bravura performance, its serious monumentality at odds with much else realized at Darling Harbour. It is shameful to record that these building have all been demolished, along with four wings of the Cameron Offices – the replacement buildings are mostly forgettable banalities – while the King George Tower and its plaza have been subject to changes that can only be described as a travesty. It pained Andrews to see his work treated so. Whatever went wrong with this country?

Paul Walker is a professor of architecture at the University of Melbourne and lead author of John Andrews: Architect of Uncommon Sense, which will be published by Harvard Design Press later in 2022.