The last architecturally designed fire station I visited was Zaha Hadid Architects’ deconstructivist offering at the famous Vitra Campus in Germany. At one point, our guide stopped the tour and asked if anyone could tell him which of the surfaces in the room was perpendicular. The answer was none of them. Queensland’s Wide Bay region is a considerable distance from Weil am Rhein, figuratively and geographically. The broad arterial road of Alice Street eases into the historic town centre past timber cottages, fast-food restaurants and tilt-up retail offerings. The site of Queensland Fire and Emergency Services North Coast Region Headquarters and Maryborough Fire and Rescue Station appears shortly before Alice Street overruns the city centre and emerges into a low-lying landscape of sugarcane fields. The eclectic setting is somewhat reminiscent of Vitra’s curious assemblage of disparate architectures, with the expansive car park of Station Square Shopping Centre, low-density suburban allotments and a pair of car dealerships gathered nearby. Maryborough’s previous fire station, an elegant brick building constructed in 1951, retains its prominent corner location. The recent additions by Kim Baber Architect flank the original structure, projecting asymmetrical wings along two frontages. Like Zaha’s fire station, this refurbished and expanded building confidently projects its ambition, though the substance of these ambitions is considerably different.

The city of Maryborough was founded in 1847 amid a fierce struggle with the original inhabitants of the region, the Butchulla people. It soon became a prosperous colonial settlement and a major port for thriving agricultural and resource industries. By the end of the twentieth century, Maryborough boasted a rich collection of commercial and municipal buildings. Today, the city promotes itself as the “Heritage City of Queensland,” and it’s a well-deserved moniker. Despite many devastating floods – most notably 1893, 1898, 1955, 1974, 1989, 1992, 1999, 2013 (twice) and 2022 (twice) – the historic city centre retains an afterglow of colonial splendour, albeit without the thriving commercial activity to complement its charming architectural legacy.

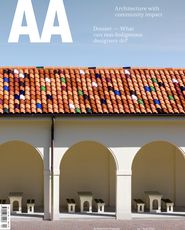

The new addition flanks the town’s original red-brick fire station, projecting along two frontages.

Image: Christopher Frederick Jones

The eclecticism of Maryborough’s contemporary inner city, including urban fabric dating from the nineteenth through to the twenty-first century, presents a microcosm of evolving attitudes towards commercial, civic and retail architecture. The remaining heritage buildings embody colonial prerogatives: projecting prosperity, driving commerce, renewing social ties and conferring legitimacy on an interloping society that looked to Europe for direction and validation, and that saw Australia as a resource to be exploited. These buildings reflected Anglo/European architectural traditions, emphasized solidity and often sought to showcase the capacity of the community to produce refined cultural artefacts.

Developments from the latter part of the twentieth century tell a different story. Many municipal buildings have shed their civic pretensions, presenting as autonomous infrastructure rather than integrated urban propositions. The result is a fractured city fringe, with car-oriented lacunae appearing in the streetscape. Kim Baber Architect’s building belongs to the contemporary, but it also shares an affinity with the buildings of yesteryear. It sits just outside the historical city centre and, like many modern buildings, is largely composed of standardized building systems. The robust and pragmatic refurbished and extended Fire and Rescue Station displays few indulgences. One notable exception is the incorporation of cross-laminated timber (CLT) construction throughout the building. Conceived as a showcase for both locally sourced timber and CLT construction and developed as a market-led proposal by Hyne Timber, XLam and Hutchinson Builders with the support of Kim Baber Architect and the University of Queensland, the project was ideally suited to Baber’s research interests. A member of the Centre for Future Timber Structures research group at the University of Queensland, Baber travelled to Europe on a Gottstein Fellowship in 2016, and he visited several exemplary CLT buildings. His research attracted the attention of Hyne Timber and led to an invitation to develop concept proposals for the project. The resulting building is progressive and forward-looking, recapturing some of the civic ambition that characterized municipal buildings of a previous age. By adopting alternative construction technologies and reconnecting with local material supply and production chains, the regional headquarters reduced the carbon emissions otherwise incurred through construction by an estimated 1,742 tonnes.

This is an admirable achievement in a building with strict operational requirements. Firefighters are allowed two minutes to transition from deep sleep to sitting at the wheel. In that time, crews need to be dressed and equipped, appraised of the situation at hand and poised for action. Sadly, this transition no longer involves a pole (a casualty of OH&S), but it does include a bold red slippery slide reminiscent of a Hungry Jack’s playground. A suitably stoic firefighter assures me that it is “very fast,” although we aren’t permitted to test the dynamics. Another pragmatic constraint for the building design, arising in response to elevated instances of cancer within the firefighting profession, is the strict control of contaminants. Modern stations are separated into multiple zones, ensuring that clothing and other equipment used in the field do not enter restricted zones. These factors govern the arrangement and layout of the operational side of the building.

The traditional firefighters’ pole has been replaced by a “very fast” slippery slide.

Image: Christopher Frederick Jones

The opposing wing of the building, which houses regional and area office staff, corporate services and emergency management personnel, includes an impressive first-floor situation room dedicated to remote monitoring and coordination of crews across the North Coast region. Here, the presence of the CLT fabric is more prominent, exposed on wall and ceiling surfaces to good effect. The inherent beauty of the timber grain and wood tones admirably accents the elegant space planning.

Externally, the regional headquarters appears to exhibit a greater degree of formal ambition, with a taller “tower” element offset by a curved corner and cantilevered second-storey overhang. However, this too is a clever manipulation of pragmatic constraints by the architect. The tower is equipped as a training facility, the curve in the facade accommodates a mandatory setback for vehicular sightlines on the side street, and the cantilevered second storey offers ample shading to the glazing on the north-facing elevation.

Making clever use of space and site, a “tower” is equipped as a training facility.

Image: Christopher Frederick Jones

At the centre of the building ensemble sits the antecedent brick fire station. In keeping with the two new building wings, this structure has been efficiently reoccupied with minimum fuss. The three original engine bays on the lower floor are now converted to a modest display and events space. This small indulgence allows the public to enter the building and view a charming collection of artefacts retained by the Maryborough branch. The space also accommodates periodic public events and can open onto a new-roofed, external terrace appended to the rear of the building.

The upper floor originally served as the fire chief’s private residence. While this practice has been discontinued, the rooms are still used as crew “rest and recline” areas. As Baber points out, this permits the presence of inhabitation to animate the facade of the building. An occasional figure on the balcony, lights glowing at night or a flicker of movement provides a subtle reminder of the life within.

A hard-working design with few opportunities for architectural indulgence, QFES North Coast Region Headquarters and Maryborough Fire and Rescue Station is very much a project of its time. The one overt architectural statement of the project – the timber construction technology employed – is ethically sound and elegantly integrated. This is an everyday kind of building intended to serve a community, enriched through thoughtful and responsible design practices. In a cultural and political environment where risk mitigation and economic pragmatism are often the principal propulsive forces in the architectural commission, this building reminds us of both the challenges we face as architects and the potential for our profession to retain its relevance as a force for social good. As we enter a new age of social and ecological imperatives, we must continue to reassess the metrics used to measure success. An engraved commemorative slab of timber, produced to mark the completion of Maryborough Fire and Rescue Station, succinctly distils this principle. It reads: “Timber in this building equals 500 m 3 of locally grown pine, representing a saving of 1,742 tonnes of carbon compared to conventional building materials, the equivalent of 375 fewer cars on the road each year.”

Credits

- Project

- QFES North Coast Region Headquarters and Maryborough Fire and Rescue Station

- Architect

- Kim Baber Architect

Qld, Australia

- Project Team

- Kim Baber, Lachlan Whitaker, Bidisha Roy, Daniel Foote, Paul Lee

- Consultants

-

Acoustic consultant

PKA Acoustic Consulting

Builder Hutchinson Builders

Civil engineer Engineering Solutions Qld

Hydraulic engineer Engage Consulting Engineers

Landscape architect Andrew Gold Landscape Architect

Project manager QBuild

Services consultant Cushway Blackford Consulting Engineers

Structural engineer Bligh Tanner

Timber engineer XLam

- Site Details

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Commercial

Source

Project

Published online: 24 Aug 2023

Words:

Aaron Peters

Images:

Christopher Frederick Jones

Issue

Architecture Australia, July 2023