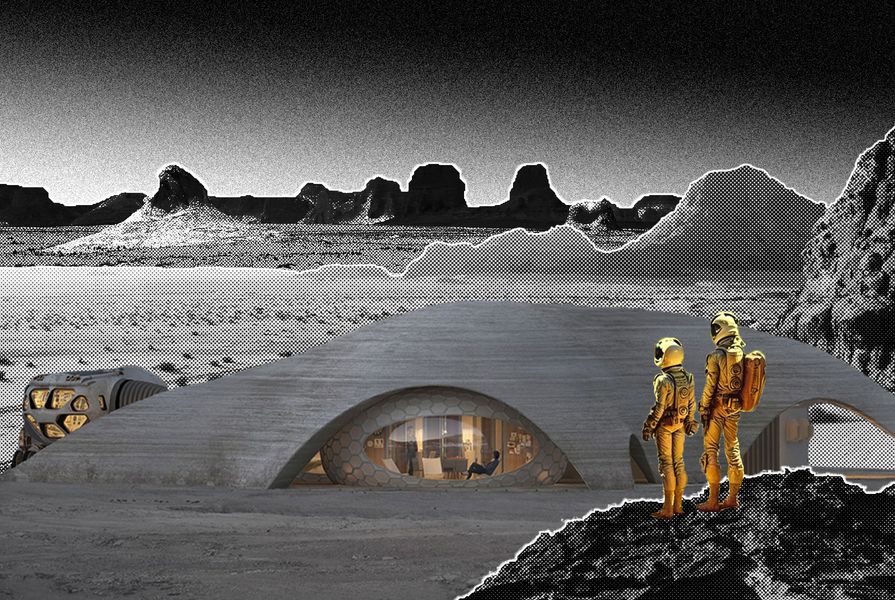

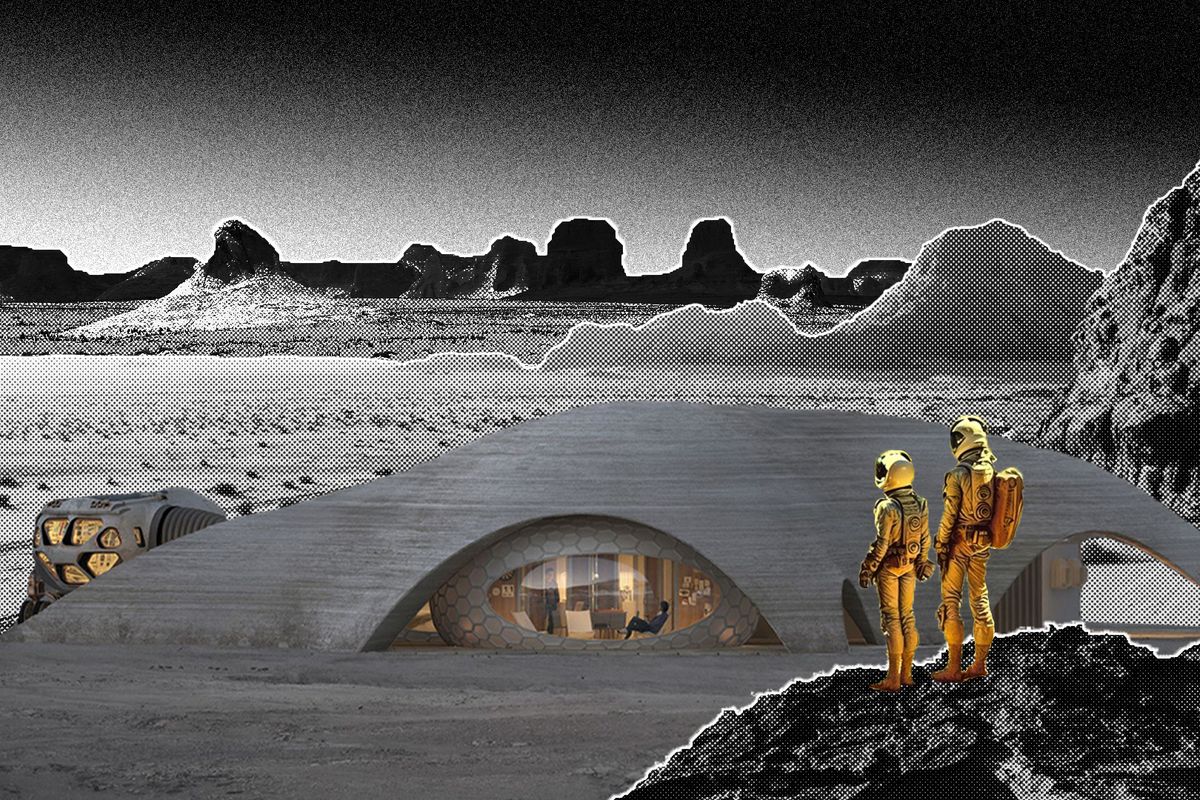

“I became an architect,” says Bjarke Ingels, “because I had heard that architects work with space.” He’s punning, of course. But here’s his chance. The Bjarke Ingels Group’s (BIG) $140-million, 180,000-square-metre model Mars-town in the Dubai desert is just one entrant in the unofficial competition to design the new, extraterrestrial world order. Everyone’s at it. Indeed, so many architects are having a go that the term “space race” is gaining a whole new meaning. Curiously, though, a sense of space is the one thing these new settlements lack.

Most proposals look remarkably like those domed space-age dreamings from the 1960s, and the subsequent domed and sandy film versions in the Star Wars genre. This is surprising, given the range of architects involved, but also unsurprising, given the challenges of sustaining life without breathable air, adequate gravity, liquid water or, by and large, survivable temperatures – not to mention toxic soil, frequent dust storms, 100-kilometre-hour winds and lethal cosmic radiation that penetrate most building materials.

Mars Science City by Bjarke Ingels Group.

Image: Bjarke Ingels Group

Such schemes include, naturally, Foster and Partners’ proposition from 2015. Foster postulates a chronology, as well as a spatial schema, with human arrival on the Red Planet preceded by months or years of robotic effort to dig protective craters, construct solar farms and 3D-print protective dwellings.

Foster’s proposed construction material is Martian regolith (the loose soil and rocks found on the planet’s surface). But other materials are also under consideration. For their Ice House, New York’s Clouds Architecture Office and Team Space Exploration Architecture deploy what in Mars-talk is known as “water ice” – to distinguish it from the frozen CO2 that makes up much of the ice on the planet – as a radiation shield. The winner of NASA’s 2015 3-D Printed Habitat Design Competition, Ice House creates an external igloo-type ice skin, pierced by inflatable windows that are filled with radiation-shielding gas. Within this rather lovely translucent beehive sits a series of inflatable living quarters – “a spectrum of private to communal interior spaces.” Lush, vertical hydroponic oxygen-gardens provide food, recreation and mental wellbeing.

Mars Ice House by by Clouds Architecture Office and Team Space Exploration Architecture.

Image: Clouds Architecture Office and Team Space Exploration Architecture

More recently, in 2019, Warith Zaki and Amir Amzar proposed a bamboo colony called Martian SOL, or Seed of Life. The idea is that bamboo, which is one of the few plants that can propagate without pollinators, will grow well in the CO2-rich atmosphere. Water, thawed from ice, will be pumped into the bamboo and refrozen, creating “a natural structural reinforcement and a second layer of protection against cosmic and solar radiation.”

A year earlier, Hassell and Eckersley O’Callaghan’s Mars Habitat project followed Foster’s lead by proposing a succession of pioneer-robots (scout-bots, dig-bots, build-bots and fuse-bots) to 3D-print an undulating blanket of fused regolith to protect a set of pressurized inflatable residential pods. Life here, coos the voice-over, is “more than simply surviving … Earth-independent but lifestyle-rich.”

Mars Habitat by Hassell and Eckersley O’Callaghan.

Image: Hassell and Eckersley O’Callaghan

Turns out, BIG’s vision is, well, bigger. Commissioned in 2017 by the Dubai Future Foundation to design a Martian city for 100 years hence (Ingels says it will actually take 200), the Danish architect paints a more holistic vision: we’re all vegan, using plants to turn CO2 into oxygen and bots to excavate radiation-sheltered dwellings protected by a combination of inflatables and printed regolith structures.

In hardware terms – as architecture – these proposals fill me with dread. To live wholly inside pressurized suits and pods, controlled by a self-regulating oligarchy of self-selected pugnacious primates and sans forest, oceans or anything wild, strikes me as a nightmare scenario, even less appetizing than a permanent diet of spirulina powder and freeze-dried grasshoppers.

The pundits are predicting 2024 as a big year for space. Quite apart from the extraterrestrial ambitions with which every second billionaire feels obliged to accessorize, NASA is reportedly planning to send astronauts deeper into the solar system than anyone has ventured in half a century, with a view to permanent settlement. Russia and China, apparently, ditto, not to mention India and Japan.

This means that decisions about what kind of world we’ll make out there – by whom, for whom and with what in mind – will need be taken, and quite soon. But this space race promises to leave a garbage-trail of issues in its wake.

Mars is an extremely hostile environment. The average temperature is -62 degrees Celsius, with some days dropping to -152 degrees. How does bamboo grow at 100-below, especially based in soil whose perchlorate levels are toxic to all plants except the common water hyacinth and a few bacteria? (Studies show that plant growth rate in such soil is reduced to one-third, even in otherwise optimum conditions.) On the other hand, how will ice shields fare on the days that reach +20 degrees (a classic Danish summer, as Ingels blithely notes)?

Then there are the environmental impacts of space travel: massive emissions of soot, carbon dioxide, water vapour and nitrogen oxide (all warming agents), plus major ozone depletion. I have no problem with the Musks, Zuckerbergs and assorted oil-rich princelings removing to the far corners of the galaxy, if they so choose. Indeed, exile into nothingness seems fitting. But the thought of the world’s aggressors – nations or individuals – squabbling for the right to rape the next planet as brutally as they have the last is at least as disturbing as those tiny, confining space pods.

Is storming off to new planets a valid response to having wrecked this one? Why leave the restoration of planet earth to those least responsible for its wreckage and least able to bear such a burden? And, beyond all that, do we really want our war on nature taken to infinity? After all, it’s a war we cannot win – if we win, we die.

Already, on earth, the primate urge to dominate both nature and each other is reducing our once-diverse cities into ghettos of the rich and our species-rich planet to a depleted wasteland. No-one actually wants this; it’s just business. But now, these same primates, freeing themselves from the moral responsibilities of home, gird their loins to terraform vast new worlds into the same old frontiers of rape and pillage.

Consider the dystopian parable of Snowpiercer, a TV series based on the 2013 film directed by Bong Joon-ho and the 1982 French graphic novel Le Transperceniege. Set in a frozen, post-ecocidal world, Snowpiercer postulates a 1,001-carriage train that, carrying the last remnants of humanity, must constantly circle the earth to keep them alive. Not surprisingly, it becomes a tale of class-based cruelty and the abuse of power.

Might we avoid such repetition? Could new planets instead inspire us to turn over a new leaf? Ingels preaches seductively of “our galactic destiny,” picturing our grandchildren gazing out at “the tiny blue dot” they used to call home with a sense of “universal citizenry.” But what are the chances? Ingels speaks in the same breathy tones of the quantum of Martian “real estate.” But wait. Isn’t there work to be done here, first?

It is still possible – just – to imagine (outer) space not as property, to be owned, fenced and fought over, but as something closer to the Modernist idea of “space” – a free-flowing landscape, open, shared and liberative.

We’re smart, this self-named Homo sapiens sapiens. We’re capable of learning. COVID taught us the value of community, and climate change the importance of circularity. But the brief that confronts us now is bigger: to design a new, cleaner, fairer, lovelier roost for the species. An entire synthetic ecosphere. Are we that smart?

French architect and artist Françoise Dallegret produced drawings to accompany Reyner Banham’s 1965 article title “A Home is not a House” for Art in America, April 1965.

Image: Francoise Dallegret

Back in 1965, Reyner Banham and François Dellegret proposed their Un-House, which postulated that in a fully-serviced bubble, humans would no longer need walls, fences, rules or clothes.1 Even if we are not quite ready for that, surely we can avoid polluting these vast new frontiers with our same old behaviours? Surely it behoves us to get our own mental and moral landscape in order before turning more of the galaxy into real estate?

- Reyner Banham and Françoise Dallegret, “A Home is not a House,” Art in America, April 1965.