I approach with caution a contribution to an issue of Architecture Australia whose theme is the suburbs. I grew up in the western suburbs of Sydney and carry with me a significant amount of unresolved rage about the inequality that they exploit and have now come to symbolize. I used to despair when architects ignored and dismissed the suburbs, but I despised it when they began to fetishize them as an exotic “other.”

Of course, suburbs have always existed. Ildefons Cerdà devoted a chapter to them in his book General Theory of Urbanization (1867). He understood them as a complement to the “urbs” – his conception of urbanization, derived from the term urbum, the plow used by the Romans to mark the line of enclosure when a city was being founded. He described the suburbs’ relationship to the urbs as “… an indispensable accessory, an unavoidable appendage, a necessary complement.”

The co-dependency that Cerdà described has never seemed to be a characteristic of Sydney’s north-western suburbs. From their infancy, they were detached and isolated – set adrift without transport, walkable streets, cultural infrastructure or protections for their subtle landscape plains and remnant indigenous forests. Now you can sense the emergence of a relationship of exploitative dependency, as the density and infrastructure that increasingly intransigent inner-urban populations are no longer willing to absorb within the core sees the rise of the “Third City,” the “Aerotropolis” or the “Western City” of the heat-scorched plains. In recent months severe floods have reinstated their implacable natural boundaries, reminding us of just how far the ecological limits have already been breached.

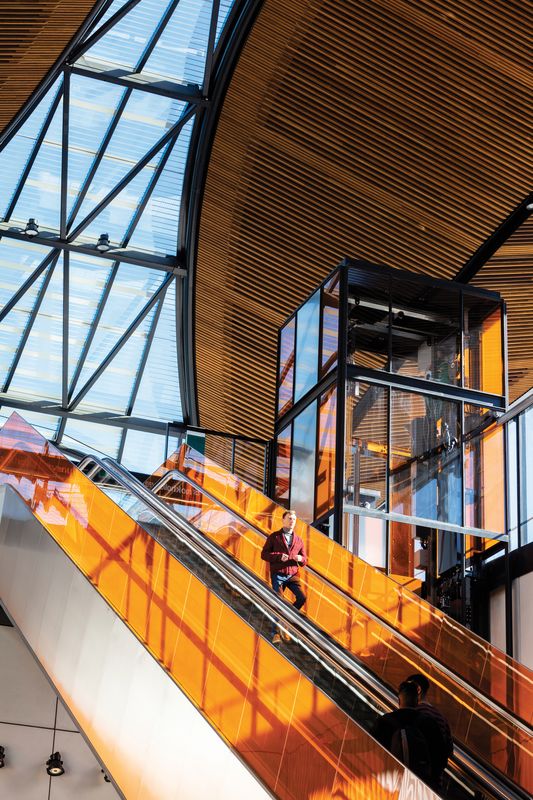

Movement through the stations is orchestrated in a different way at each station, depending on the topographic and urban conditions. Pictured: Rouse Hill Station.

Image: Brett Boardman

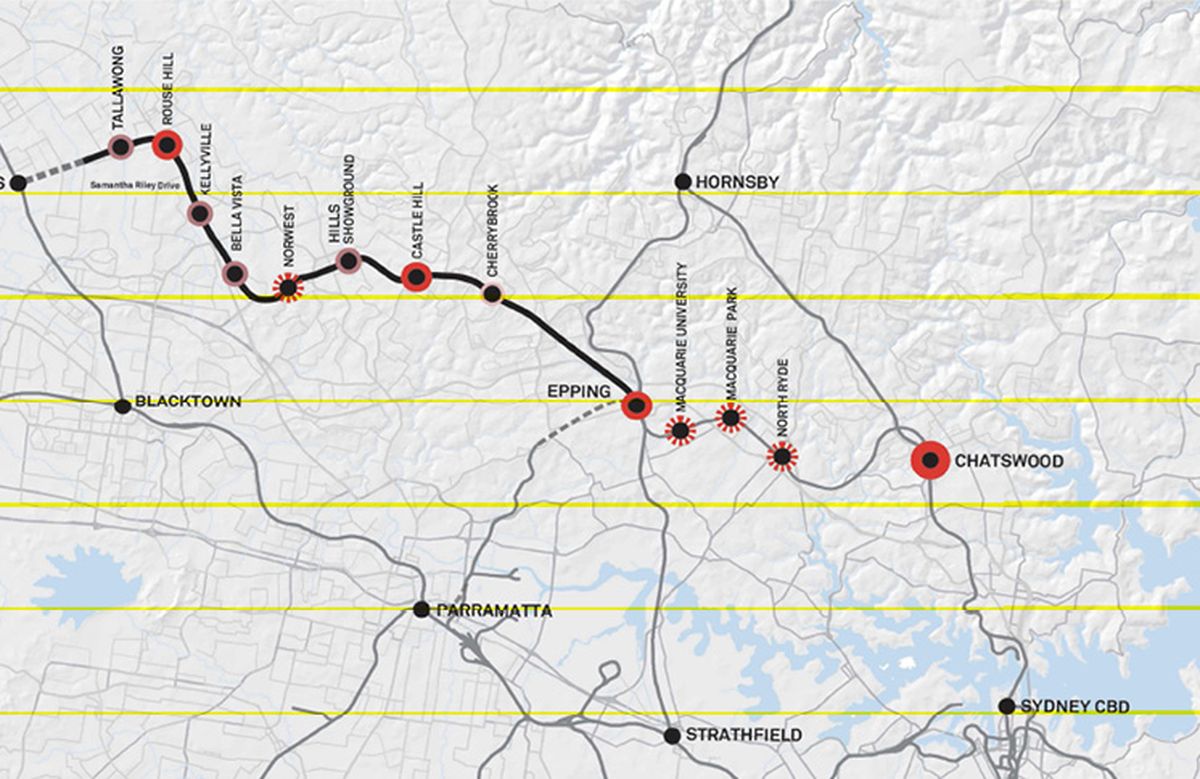

The Metro North West Line (MNW) by Hassell in collaboration with Turpin Crawford Studio and McGregor Westlake Architecture picks up the frayed ends of the Epping-to-Chatswood heavy-rail link and runs out to what we may for a limited time still call the “suburbs” of north-western Sydney. You may remember these same Epping-to-Chatswood intermediate stations, also by Hassell, from their winning the Sir Zelman Cowen Award in 2010. That line was originally launched as the Parramatta Rail Link, which, in quintessentially Sydney fashion, never quite made it to Parramatta.

The more cautiously monikered MNW serves a part of Sydney that has been starved of public infrastructure of every meaningful kind, but particularly public transport and cultural and civic facilities. Thus the completion of this line is long overdue and highly significant – even if, in a nod to past practice, it failed to make the last three tantalizing kilometres that would have linked it into the metropolitan network at both its northern and western ends.

Hills Showground Station, which establishes an integrated transport interchange, caters for significant growth and intended future developments.

Image: Sydney Metro

There remains debate about the choice of mode for this line. Some favoured heavy rail for its greater passenger capacity, speed and suitability to the long distances involved, in terms of both the overall length of the line and the distance between stations. Conversely, metro tends to be the preferred choice for dense city cores, where its single-deck, quick-turnover format allows people to move rapidly between the dense pockets of major cities with high service frequencies – think Singapore, Paris and Barcelona. There are compelling arguments for both choices, but one suspects that the New South Wales government’s commitment to metro should be interpreted as a signal of just how much density this and other metro corridors are going to be asked to deliver over the long term. This line, its City and Southwest line extension, the Metro West line and the Western Sydney Airport line confirm Sydney’s definitive shift to a “polycentric” growth model.

The metro cuts a geographical transect through Sydney, but also a socioeconomic one. As you move westward, average incomes decrease and summer temperatures rise. Subdivisions become newer, the tree canopy thins and car dependency increases. In the urban core the metro buries deep beneath older, refined and leafy northern suburbs, emerging into an open cutting at Bella Vista before rising above ground on an elevated viaduct at its western end and returning to earth at the Tallawong terminus. For a passenger, this gives the project a distinct experiential structure as you encounter “below,” “in” and “above” ground conditions along the trip, but it also reflects a level of political pragmatism in economics and planning. Some parts of Sydney’s population squeal louder than others.

At Cherrybrook Station, which services a large residential area, the entry provides space for community activities.

Image: Ian Hobbs

The relationship of the line to the ground plane most powerfully characterizes the station architecture, where “underground,” “cut” and “elevated” conditions lead to a beautifully judged trio of sectional experiences and movement patterns from metro to surface. The strategic sophistication of the approach speaks to Hassell’s long refinement of this type, dating from the Olympic Park Station more than two decades ago.

Hassell principal Ross de la Motte describes the competing tension between regularity and particularity. A suite of repeatable elements is necessary to manage such an extensive undertaking, but the kit of parts needs to permit flexibility to speak to an array of places and conditions. De la Motte and his team reflected carefully on the Epping-to-Chatswood stations, acknowledging their strength, but came to the view that they wanted to elevate the sense of specificity in their works on MNW. To that end they worked with public artists Turpin Crawford Studio and McGregor Westlake Architecture in developing a narrative that could more particularly reflect the character of each station along the line. Working with the region’s agricultural history and its forest clearings of gridded orchards, they developed a chromatic gradient and landscape narrative that leaven the muscular intelligence of the infrastructural components.

The inner-urban stations orchestrate movement vertically from bored tunnels up toward daylight. They are telescopic in section and labyrinthine in character. You arrive on the platforms into a crisply defined rectangular room with intensely coloured artificial light in strips along the platform edges. As you move up to the concourse level, the scale inflates and broadens and the rhythm of the halls’ emphatic structure is articulated with mirrored periscope insertions that refract sky, accent colour and glimpses of terraced gardens above. Light is cast and reflected around the concourse hall in patterns that subtly animate the daily commute as they shift with diurnal and seasonal sun movements.

The metropolitan- scale Light Line Social Square public artwork, a collaboration between Hassell, Turpin Crawford Studio and McGregor Westlake Architecture, is integrated into the architecture, landscapes and public plazas of the new stations.

Image: Brett Boardman

Above ground, these stations announce their entries with curved, clear-spanning canopies articulated with banded glazing and hardwood soffits. The extensive air-handling plant and servicing volumes are generally decoupled and set apart, which allows the canopies to be read purely against the chequerboard garden terraces, skylights and colour-matched planting that will, over time, help to frame the stations as busy social squares. The sculptural intent of the ensemble will become more powerful as surrounding development defines the “urban clearing” more categorically.

The stations in cuttings reassemble these same elements into a more landscape-oriented response. Gridded tonal plantings fill terraces beside the station platforms, most successfully where generous lateral dimensions allow the levels to open gently to connect sightlines between platform, garden, street and sky. The canopies announce station entries either centrally or at each end, and here sit into the cutting, bringing the scale down to sit a little more diminutively in the streetscape.

Architecturally, there is an unapologetic acceptance of the scale required for the elevated stations. Pictured: Rouse Hill Station.

Image: Brett Boardman

It is in the elevated stations that the project most powerfully answers the question of the civic character that might emerge from the particular conditions of this part of Sydney. It does this through the unapologetic acceptance of the scale that results from their elevated condition. In these suburbs the “civic” competes with the brutal scale of arterial roads, the illuminated ensigns of fuel and fast food, the recreational cathedrals of Bunnings and the slack-jawed kitsch of the Ettamogah Pub. In this context, pretensions to civic “decorum” are cultural roadkill.

The elevated stations wrap the viaduct in striated colour, making concourse halls that are tectonically lean but spatially substantial. Colour is cast both ways – across the concourse floor as a tracery of structural leadlight and outward as an illuminated billboard after dark. Mist gardens and more intimate gathering spaces in eucalypt groves, with customized furniture that plays on the segmental geometries and colours of the orchard fruits, all contrive to define public character with a sort of tough lyricism that manages to avoid both condescension and conceit.

I asked my sister, who has lived in the north-west of Sydney all her life and has even less tolerance for the conceit of architects than I do, for her opinion of the metro stations. She told me that she liked them a lot because “they feel like they should be in the city.” Clearly an endorsement of the effort and investment – yet it’s so jarring that people living in this part of Sydney automatically think that civic aspiration is not something owed to them, but the privilege of urban dwellers.

That Metro North West Line has been executed with this level of public aspiration and conviction really matters, but it is just the beginning of a larger story. It is the ensuing layer of development that MNW will unleash that will reveal whether we are truly invested in creating the Western City or simply outsourcing inconvenient inner-urban problems. Are the framework, policy and oversight in place to effectively channel the commercial onslaught that is to follow? We should all be watching this space very, very closely.

Credits

- Project

- Metro North West Line

- Architect

- Hassell

Australia

- Project Team

- Ross de la Motte, Geoff Crowe, Keith Allen, Chris Lamborn, Chris Carr, Jason Hammond, Peter Monckton, Yee Woon Juen, Tom Withecombe, Michael Luders, Michael White, Phillip Meehan, Shane Marshall, Adam Griffin, Alex Chow, Allison Hortz, Bo Zhen,, Catherine Zhuang, Emma Townsend, Esther Kay, Joe Li, Kutay Ozay, Leo Carson, Liam Fitzgerald, Neil Bartlett, Richard Huxley, Rocco Dascoli, Troy Cook, Angus Bruce, Julieanne Boustead, Anthony Charlesworth, Anne Lucas, Andrew Ewington, Ben Charlton,, Callum Bryan-Mathieson, Craig Tennant, Carine Macleod, Chris Tidswell, Grace Rummery, Hanh Nguyen, Riley Field, Matthew Watson

- Consultants

-

Acoustic consultant

Renzo Tonin and Associates

Civil, structural, mechanical and electrical engineers Mott MacDonald, KBR, SMEC

Compliance and accessibility McKenzie Group

Documentation delivery support Atlas Industries, Assemble, Ridley and Co

Environmental design Flux

Lighting design WSP

Public artist Turpin and Crawford Studio

Rail systems UGL

- Aboriginal Nation

- Built on the land of the Bidjigal and Caramaragal peoples.

- Site Details

-

Location

Sydney,

NSW,

Australia

Site type Suburban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Completion date 2020

Category Public / cultural

Type Infrastructure

Source

Project

Published online: 10 Aug 2021

Words:

Laura Harding

Images:

Brett Boardman,

Christopher Frederick Jones,

Hassell,

Ian Hobbs,

Mark Syke,

Sydney Metro

Issue

Architecture Australia, July 2021