Lena Kleinheinz and Martin Ostermann of the Berlin practice Magma Architecture came to Australia in 2017 as part of the Droga Architect in Residence program.

Ostermann was the official “architect in residence,” accompanied by the sculptor and architecture historian Kleinhein, but they worked as a team during their months in Australia, running student workshops, giving lectures and exploring notions of temporary, adaptable architecture on Australia’s fast-changing coastlines.

In this freewheeling conversation they talk climate change, the pandemic and the choice between adapting to change or building fortresses to keep it out. They also explain how the residency has had a greater impact on their practice than they had initially imagined.

Josh Harris: Part of the stated goal for your Droga residency was “to challenge the permanence of architecture.” Could you explain a little how you tried to do this during the residency?

Lena Kleinheinz: One of the main ideas was to think about how architecture can adapt to changes that happen around it. We thought a lot about how global warming might change our environment and how we could produce buildings that are able to adapt to that.

We started out in Perth and did a workshop at the University of Western Australia. One of the first things that was really interesting that came up was the idea of having two possibilities. Either you say, if the environment changes, then architecture has to become more like a fortress and very un-changeable, or the other possibility is to say that we build something that goes along with the changes.

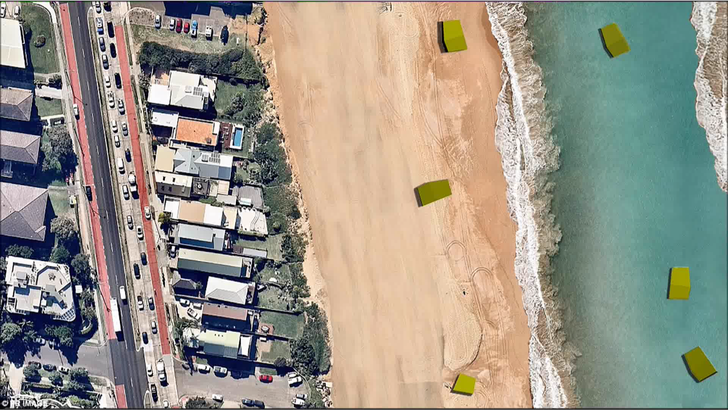

A concept for a temporary beaches, floating on the sea.

Image: Magma Architecture

Martin Ostermann: The reason we came to Australia was that we were interested in mobile architecture and temporary architecture. We had done projects in this field, and we were realizing that we had to start looking at architecture differently. Why is everything static? Why is everything permanent? Can’t architecture be something that is temporary, changeable, adaptable? Why is architecture so different from how we dress and how we live in other ways? In Australia, what we found interesting is that most habitation is around the shoreline, with something like 80 percent of the population living with 50 kilometres of the coast. So the upcoming changes that global warming poses will have a great impact, and we will have to adapt architecture to cope with that. We had some very interesting conversations with students, and with the oceanographer Charitha Pattiaratchi, who had a huge influence on our work.

LK: I’m not sure he knows of the impact he had – he was probably a bit surprised to be invited to the architecture faculty! One of the things that he said is that people such as architects, and everybody else, imagine global warming as something that’s very slow and steady, you go up a quarter of a degree or half a degree and nobody can imagine that it really means anything at all. But what he said is that what we have to expect is not soft change, but more extreme weather conditions – storms, floods. It’s not something that rises slowly, it’s something that makes everything fall apart.

Another proposal for tumbling structures that would move with the incoming tides and waves.

Image: Magma Architecture

The Thames Barrier in London is one attempt to build a fortress that can keep out the environment – I don’t know how many billions they spent on that, but [with rising sea levels] it’s only going to last another couple of years and then it won’t be good enough anymore.

JH: During that visit to the University of Western Australia, you ran a workshop with students and they came up with these fantastical designs and proposals for temporary forms of architecture. Do you remember what some of those proposals were and what that process was like?

MO: It was fantastic. It’s a very innovative school. We worked with students who had taken some strange courses that allowed them to build mechanisms, which is knowledge that we didn’t expect from architecture students. They created these strange creature-like architectural proposals, which were fantastic to look at. And the great thing about Perth is the closeness to the sea, which meant that we could see how they were functioning. Some went to the beach and did testing there; we also had a lot of water inside our studio – there was a lot of splashing around. There was some very strong work, which stayed with us.

LK: Yes, one proposal was for these pontoons, that would float on the water and lift things up, so that the entire geometry of the structure that they built on would change with the movement of the water.

MO: Another proposal took the notion of waves as a movement to transform the architecture, so that the building would slowly move along the beach. The idea usually is that if the sea level rises, and the water is coming more and more into the landscape, then architecture has to retreat. This was a more poetic approach.

Magma Architecture presented its schemes in a multimedia exhibition in Sydney, which included a series of short films.

Image: Magma Architecture

JH: Did this workshop, these proposals have an impact on your own research?

MO: To tell you the truth, this was a real starting point for us in our research. We now do a lot of research into how to deal with these kinds of changes. We’ve been talking to more oceanographers, and conducting research on adaptable buildings, responsive skins, active facades, and a lot of that is driven by what we started to research in Sydney.

LK: This whole idea of research was always something that we felt was missing in our office, because you can’t research in an office, it’s not possible. Clients don’t want experiments, they want safe and economically viable proposals. So, one of the reasons why we wanted to do the Droga residency was to make some space to think in that way, which we could never do in the office.

JH: Most of the other Droga residencies were single architects – whereas you each brought expertise from different fields. How did you work together during the residency?

MO: We did think about the other residents who were there alone; you could imagine sitting up in the apartment, looking out the window, writing. It’s a kind of ivory tower, you’re inside this space, up in the sky, above the city. It would be a kind of poet-like environment.

But we had a different setup, with us two plus our child. We always think that it’s important not just to be there, we don’t think that it’s good to just work as an individual, to sit in a quiet environment, tucked away. We were very much out there, trying to talk to people. That’s the way we can work creatively, because it’s an exchange of ideas, it’s never just coming out of our own minds.

Inflatable platforms filled with sands perform the function of today’s beaches, acting as Australia’s “backyard.”

Image: Magma Architecture

JH: I understand you created a multimedia installation in Sydney at the end of the residency? Could you explain what that was about?

MO: We had done a couple of student workshops, some of the students came over from Perth, and so we had this amazing exhibition showing the student work, which basically represented the research we were doing together with students in the workshops. And then we worked on developing this research on Australian beaches because we were interested in the cultural value, the cultural iconography of beaches in Australia. If the sea level rises within a couple of years there won’t be any beaches anymore. We thought that would be a cultural loss that would have a huge impact on the identity of the country.

LK: The way that life takes place on the beach and becomes part of the city grid – it’s not just a beach, it’s a street, it’s a backyard, it’s a balcony, it’s an extended part of the city. The idea that that would be cut off, it’s almost like the city wouldn’t work anymore. We thought that we needed to make a structure that could take over the role that the beach played.

MO: We developed ideas of what would be the response [to rising sea levels], but which would also highlight what the effect of that change might be on architecture, on the landscape and environment. One proposal was to conserve those beaches by making them temporary. We thought about how we could have these temporary beaches floating on the sea, but still have them acting as a backyard, as Lena said. We looked at inflatable platforms with sand, and then we developed a film that of came out of our workshop with students in Perth, that depicted these tumbling structures that would move with the incoming tides and waves; the space inside would always be different depending on how it would sit and how it would be affected by the sea.

The temporary beaches would be moveable, and would respond to changing conditions.

Image: Magma Architecture

LK: It has no foundations; it’s just like a pebble that goes back and forth on the beach.

JH: At the time of the residency, you talked about a globalized society that is in a constant state of flux – and proposed an architecture that can adapt to this constant change. Since then we’ve seen some really drastic global changes – I wonder if the impact of the pandemic has confirmed for you the value of this kind of approach? Has it had an impact on your practice, on your thoughts about how to respond to climate change, for instance?

LK: [Climate change] seems to have been overshadowed by the pandemic, but it hasn’t gone away. The huge Fridays for Future movement that became very visible and very strong, gave us the idea that there is a younger generation that’s really going to [lead the way]. And we can also sense that now, with the younger people that come to the office, and also Martin’s students, that this is a subject that they are really burning for. And I think that’s so important in a way, and I somehow hope the whole pandemic thing will just go away, I don’t know whether it will, but we have so many other important things to deal with.

If this is the future that we have, let’s say one pandemic, every three years or every five years, maybe we get a bit better at dealing with it, but if that becomes what we have to focus on, what will happen to all the other really important subjects that we should be dealing with?

The pandemic, of course, has something to do with the way that we’re treating nature, it’s not apart from that, but I think we really need to make sure that we don’t lose track of global warming.

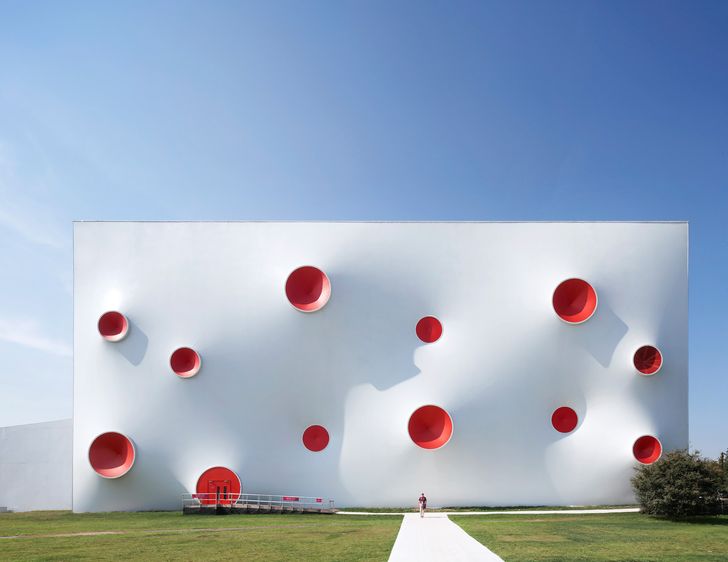

Olympic Shooting Arena by Magma Architecture, an example of the practice’s exploration of adaptable architecture.

Image: Hufton Crow

JH: Anything other thoughts on the residency?

LK: I was sorry to hear that it’s not being continued, I don’t know what the exact reasons behind that were, but I think it was a really great program.

MO: There are a lot of artist-in-residence schemes, but an architect-in-residence scheme is quite unique. And I thought it was fantastic … you can meet all these people and exchange culture, and the residency was very well organized in terms of meeting people.

LK: I think it’s much more difficult to do an architect-in-residence program than an artist-in-residence program because artists work on their own. It’s much more difficult to develop a program that works for architects, because they’re much more part of a team. I also think in that sense it might even be more valuable because you have to think in a completely different way. I really thought that it was amazing that this was being offered and being tried. We have even thought of getting a space and setting up a residency program here!