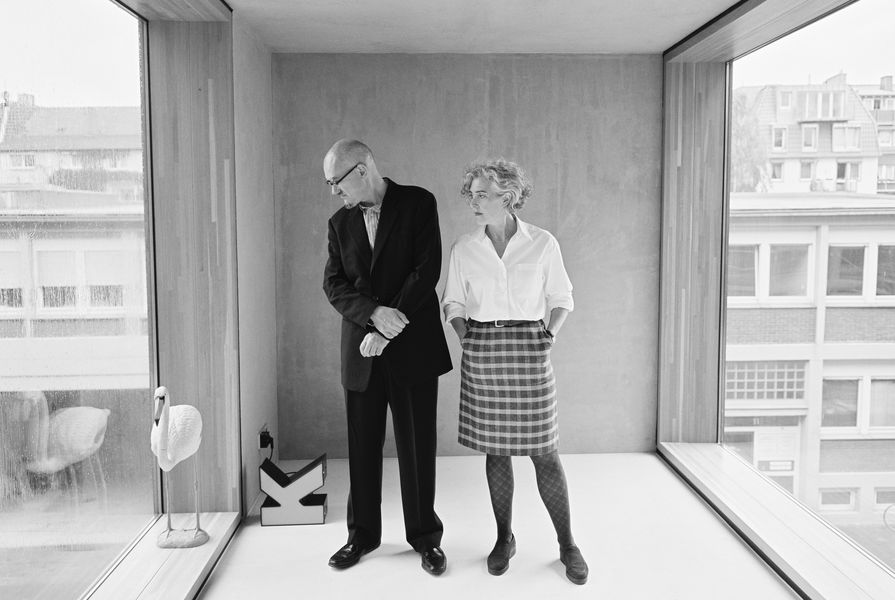

Architect Gerard Reinmuth.

Gerard Reinmuth: The Gold Medal has now been running for fifty years and despite the healthily multicultural cross-section of recipients, it is really Kerry Hill (2006) and you who stand out as the Gold Medallists who “made it” overseas. Your long-term location and sustained output in Europe is almost unique for an Australian architect and I feel that the “Australian-ness” of our award calls for a moment reflecting on your expatriate status. This might include a reflection on the value of carrying an Australian background into a European context – or as Leon van Schaik would say, the ethical issues around the export of your spatial intelligence from its original context to a new place.

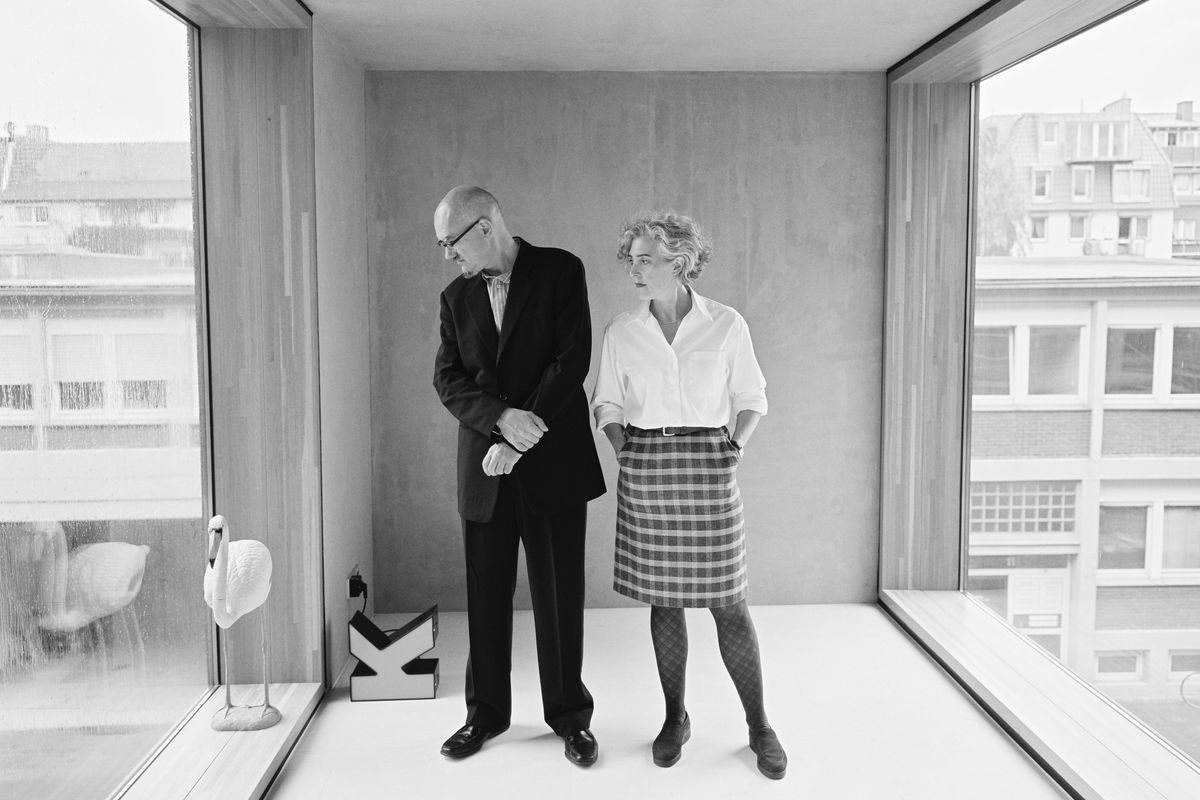

2013 Gold Medallist Peter Wilson.

Peter Wilson: The blue passport with kanga and emu on its cover is a commodious flag to travel under and seems not to have a use-by date. It has served me well during my forty-year voyage into the wide world. Ultimately one is just another citizen of the diaspora, as Edward Said once described himself. Although I have returned to Australia regularly over the years, I must confess that the Gold Medal was quite a surprise. Until that moment I had not been aware that my role in Europe had an ambassadorial dimension.

I like your quote from Leon about my exporting a “spatial intelligence”; this is perhaps more the case in relation to wide horizons and big skies. I have in fact arranged things so that my workstations in London and Germany offer distant views and as much sky as a Ruisdael or van Goyen, but not unfortunately those leaden Melbourne winter skies with that promise of a distant elsewhere, a stripe of gold lurking way off over the upper Yarra Valley.

My Australianness is certainly displaced, also mutated by circumstance. Cut loose from cultural ties and expectations, you pick up the ability to enter, grasp and operate in new locations. The first for me was the UK, where you were expected to erase your past and adopt mother country codes – not exactly a behaviour mode conducive to architecture (one perceptive British critic described modernism as “something foreign, imported”). Next came Germany, where we began to build and discovered that as an architect you have a certain public status. In Italy you are addressed respectfully as Architetto – although I could not claim to have gazed through the veil of rituals and Machiavellian agendas that accompany projects there. The Netherlands is a place where jokes in English are understood, they build sketches and we have been very happily building away there since the early nineties. Albania and Lebanon are other somewhat exotic ports of call where we have recently taken on board particular local modes of bringing buildings into existence.

Hugh of Saint Victor once laconically wrote, “The person who finds his homeland sweet is a tender beginner; he to whom every soil is as his native one is already strong; but he is perfect to whom the entire world is as a foreign place.”

On observation

GR: I want to ask you about the distinction between looking and seeing, which you have discussed in the past. For example, Gold Medallists include people like Glenn Murcutt, who famously refuses commissions overseas. In your case, where 95 percent of your practice output has been “overseas,” if I may persist in using your birthplace as the home reference, I wonder how your observation skills have changed over the course of this time in Europe.

PW: In the early 1990s we were seeing Germany with somewhat fresh eyes. At least I was; Julia had just moved back to her home town. We were loaded up with the jargon of the “critical reconstruction” of the European city – blocks, boulevards, etc. This was it, we were finally operating in and on European cities, except that what we found was that reconstruction was psychological compensation for the wartime obliteration of almost all German cities and the subsequent failure of functionalism to deliver a coherent urban texture. We were also at that time flying back and forth to Japan (workshops with Toyo Ito, working on the Suzuki House – the Japanese economic bubble had not yet burst). Our European analytic tools were useless in trying to make sense of the matrix of Tokyo. What we noted there was a sort of DNA of dispersal, elastic boundary conditions, networking protocols and an equal distribution of urban components – tower, neon sign, small wooden house, shopping mall, Pachinko Parlour – micro events that Atelier Bow-Wow later termed Pet Architecture. I sketched Tokyo and Osaka as clouds of such bits.

GR: It sounds as though you are describing something that is not just a function of being “from the outside” but rather, a trained and purposeful “productive de-familiarization,” as Zeynep Mennan once said in a review of our practice.

PW: Maybe she was referring to Viktor Shklovsky? I found myself travelling often by train across Germany – noting the bits of infrastructure, out-of-town shopping boxes, a soup of temporal markers, a sprawl that approximated the cloud format of Tokyo, but about twenty times less dense. This led to the Eurolandschaft hypothesis, that in the age of media and mobility the whole landscape functions as one huge dispersed urban carpet, “just in time” ecologies of circuitry applied to the extra-urban field. I must stress that the model was not derived from theory but was the result of direct observation, the dérive of the moving viewer.

At about that time I did another cloud drawing (To Wagga Wagga via Gumley Gumley) on my way to judge a competition in Australia. In the event dispersal of the Australian landscape, floating autonomous signifiers seemed once again to reiterate a Tokyo soup model. Maybe that is what I had been drawing all along … anyway, the operative technique is drawing, which prompts a particular way of seeing. Recently we published pages from my private sketchbooks with the Italian publisher Moleskine – a strange moment. Up until then these books had been private, my personal tool, discreet registers of being in the world, notations of where I had been and what I was reading.

GR: How are you “seeing” now, twenty years on? You must be very much a local in your context, and have had some of this earlier “X-ray vision” blunted, or at least replaced, by something else, no matter how well you can structure this deliberate de-familiarization.

PW: Through a few well-rehearsed tricks you manage to simulate a form of naive perception. On the other hand it is impossible to completely disengage analytical tools you have encountered in other disciplines – a Lacanian multivalence (Real, Imaginary and Symbolic) or the modesty and humanism of writers such as John Berger and Georges Perec.

On design, pedagogy and influence

GR: We should talk for a moment about the library in Münster, as it is such an important project. I still remember when it was completed and published – it created something of a frenzy in my peer group at university. Subsequently, a whole raft of student projects in Australia featured anthropomorphic structures, layers of detailed joinery and all sorts of embellishment related to inhabitation, while crimped copper roof profiles abounded.

PW: Many thanks for those generous words. The Münster Library seems to have been much more positively received in English-speaking contexts. For a number of political and ideological reasons it was received with a certain scepticism in Germany. The timing was unfortunate; either it was too early to be understood or it arrived too late, concurrent with 1990s minimalism (and it is most certainly a maximalist building). Even recently a minor member of the Berlin mafia lecturing in Münster pronounced our library a mistake, claiming that it should not have been built. Nevertheless, it has maintained over its twenty-year life unprecedented numbers of users – four hundred per day – and has remained either top or second in the annual ranking (user voting) for seventy public libraries in Germany.

We have learned more by observing it in use than any number of theories could teach us. It is a public building where users feel at home, perhaps due to a somewhat domestic atmosphere. At the time we had only realized domestic spaces – our own in London, the Suzuki and Blackburn houses – this was the scale we thought and worked on. It has a particular library atmosphere, as noted by Ettore Sottsass, who said as we walked through it that it feels like a library. This is because we panicked about the acoustics and lined the inside of the copper roofs with huge areas of absorptive perforated wood panels. Curiously it came in under budget, with thousands of individually drawn details. I still today wander around nostalgically running my hand over the site-welded, filled and sanded steelwork, thinking that only a madman would detail like this. The steelworkers loved it, finally a chance to show what they could do.

GR: Given this ongoing political resistance, and your comments about detailing and manufacture, would the project be possible today?

PW: Would it be possible today? Technically, yes. Laser-cutting of steel or joinery is far in advance of architects’ projective imagination. Politically – it was one of the last competitions before the reunification of the two Germanies, which meant dispatching the funds of West German cities to pay for the reconstruction of their ex-Communist counterparts. These cities no longer take on the role of public client, which represents a culturally problematic situation – a lack of answerability for the public realm.

Tightening up

GR: Your work has, over the past two decades, “tightened up” in formal terms. I think you always claimed a diagrammatic clarity for the work, but you were very clear about the importance of details that “through their use bind the occupants to the object.”

PW: Having set out with what Italo Calvino termed “multiplicity” as our strategy, we went through a few years of what he called his back-up mode of writing, “exactitude” (Mies as opposed to Scharoun). This was necessary if we were to continue our European practice. It also represented a certain maturing after the indulgent exuberances I had taught at the AA.

We were never advocates of “diagram architecture”; in my opinion it edits out spontaneity and intriguing subplot. I have always found the diagram a tautological tool – professing to have encapsulated solutions to all incumbent issues (deterministic prefiguration) and then functioning as its own dictatorial yardstick against which the end product must be measured. Our projects are not theoretically predetermined, they are evolutionary and cumulative, like the incidents (adjacencies) you mention in the Münster Library. At that time we often quoted Lyotard regarding the small narratives of practical opportunity, which today have replaced the grand narratives of theoretical causality.

“Productive naivety” is something I would advocate – an induced state of self-intoxication necessary to question the habits of convention. Even now our clients say to us, “How do you expect to stay in business with all those complicated details?” They are the ones who benefit from a building loaded with life-enhancing moments. They know full well that we are idealists whose reward is not financial – the good ones get it in the end.

The Suzuki House

GR: I have been lucky enough to visit Akira Suzuki’s house in Japan three times, once accompanied by Atelier Bow-Wow, who research a trajectory in architecture grounded in the act of inhabitation, clearly influenced by this precedent. It remains a remarkable project, perhaps better every year, and evolves through inhabitation, new layers of life’s accoutrements.

PW: The latest photos we received from Akira also show a wonderful density of encrustation, the act of inhabitation recoding the interior spaces. Akira is a very special person on the Japanese architectural horizon; his book Do Android Crows Fly Over the Skies of an Electronic Tokyo? is a classic. We recently interviewed his daughter to see if there were any adverse effects from growing up in such an idiosyncratic space, especially her 2 x 2.5-metre concrete box. How did she explain the enigmatic black silhouette on the facade? Our narrative of ninjas and the glance of information rain was certainly too much for Japanese schoolgirls. “Oh no,” she said. “I told all my friends my house is a panda bear.” More pet architecture.

City Hall + Raaks Cinema Centre, Haarlem, Netherlands, 2012.

Image: Christian Richters

Poetics

GR: Over the past decade an increasing prevalence of formal and programmatic invention has been the driving force for architectural discourse. Yet in your work the value of perception is favoured over analysis – a mode of formal invention that appears to be based more on poetics than on analytic reasoning. How do you make a claim for your work in an environment where there is less client trust in perception and a greater need to provide pragmatic analysis and solutions?

PW: I believe your question overlaps two distinct issues: how you explain your work or process to yourself or sympathetic colleagues and what you say in the marketplace of praxis. It would be overly innocent to try to interest an investor with a je ne sais quoi of poetics; the inexplicable has a dubious market value.

On the other hand I do aspire to and regularly research the auratic, the je ne sais quoi of places, their ambience. This, rather than clever textural appendages, is how buildings animate their audience. We recently completed a new city hall in Haarlem, the Netherlands. When finished, its articulated volume and tactile surface spoke a language that politicians, investors and architectural critics agreed had a certain haptic familiarity, something not foreign to the detailed brickwork of this sixteenth-century city. This was an added poetic value, something hardly discussed during planning and construction, when all justifications were pragmatic: square metres, fire escapes and rental units. It’s a question of which hat to wear to which party.

A number of respected colleagues have for some years been wearing the phenomenological hat in public, a difficult act to conclude as perception is as much a function of the experiencing subject as of the built object. I would very much like to believe in the hermeneutic potential of architecture. Commodification is the danger; before he was a fashion label Hermes was the messenger between Olympus and the world of experience.

Theorization and the speed of practice

GR: You noted in your El Croquis interview that “everything is so fast that theory gets left behind.” I suspect this was a response to the reality of the highly commercial environments you were working in at the time. Since then, things seem to have only become faster and commercial culture is even more pervasive. Over a career that has featured a healthy body of built work, how have you managed this balance between phases of intense theorization or preparation and phases of “action” with little time for theoretical positioning?

PW: This question is somewhat foreign to me; I have never considered theory something you go away and do, a sort of gas station for the next phase of production.

GR: Yes, I agree, I think I was responding to this earlier quote of yours about theory.

PW: Well, another way of considering this question would be to say that these two aspects of architecture are for me concurrent, or at least symbiotic. I have a daytime and a night-time work mode. The first is office: deadlines, the designing of buildings, or a detail for a particularly tricky corner (an enjoyable exercise, like Nabokov solving chess problems). The second is a sort of unstructured dérive amongst the books I am reading and the miniature paintings I produce as spatializations of various cultural or topological constructs – it would ennoble my studio playground enormously if this activity were to be called research. It might be a sort of “body building” for one’s spatial imagination or, as the hermeneutic philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer described it, working on the project self.

New Luxor Theatre, Rotterdam, Netherlands, 2001.

Image: Christian Richters

On procurement and the role of the architect

GR: I have always marvelled at the way your projects tell a larger story about the city. From the Münster Library to the Bridge Watcher’s House, Suzuki House in Tokyo, Luxor Theatre in Rotterdam and then the work on the Eurolandschaft, each is entangled in a specific vision for a whole city even though each is also specific to its immediate context. The works are powerful manifestos about the changing city. The periphery work that started appearing around 2000 was prescient in giving form to this hidden condition of the continuous logistics city which Europe has evolved into since World War II. Whereas someone like Koolhaas has made it a separate project to observe and document these phenomena (junk space and so on), we also have “strategic designers” celebrating their ability to interpret these spaces but without a fully developed sense of the spatial implications or the skills to test them. Meanwhile, you seem to make these observations effortlessly and humbly as part of an individual building project.

The question here is about the capacity and agency of the architect. How do you think we can better capitalize on the ability to observe such phenomena, when our fees are still directly related to a percentage of a building budget and a crowd of consultants are making an industry out of observations we make as part of our daily work?

PW: I am not very optimistic about some institutional father figure appearing to empower us architects with the responsibility of meta-scenarios. Our Eurolandschaft studies were of their time (the early nineties) and it is now a legitimate field of study – Horizontal Babylon, La Città Diffusa, Rem’s Junk Space (as you point out), Lars Lerup’s Stim and Dross coding of the American wasteland, and in Germany Tom Sieverts’ Zwischenstadt (in-between-city).

While these are great conference topics they are more difficult to implement on a strategic level of planning or city making. The planning industry in the UK, for example, is suffering an acute case of constipation, not enough visionary laxatives (or perhaps too many seductive renderings further clog the digestive passages?). The fact is there is such big money in development that a whole tribe of report writers (more legal than spatial) have moved in to take their cut. This includes the Urban Syntax sect, who graph commonsense observations about how people move around cities. I was once in hot water for referring to this discipline as Urban Voodoo.

We recently found ourselves working on a masterplan for the Adidas World Headquarters in Bavaria. Our technique was scenographic and open-ended – elements such as a 500-metre lake for rowing could be invented overnight (our landscape architects advised that water was cheaper than landscaping and planting the topography). A developer was making a pitch to a global player and what we provided was the visual scenario. It used to be that Dutch planning offices would commission recent graduates to invent a scenario for a particular site or corner of the city. It was a harnessing of talent, a first step into the profession. What made it possible was that Dutch planning is not only regulatory but also anticipatory – planning rules there have a visual component (an image quality plan).

I am not sure if I have addressed your issue of procurement. I have always believed there are two procurement paths. Either one plays golf, smokes cigars and joins Rotary or one puts one’s trust in the merit of one’s product. This we have been lucky enough to do, in an environment where all public buildings must by law be the subject of architectural competitions.

The role of the academy

GR: Reflecting on your career, the evolution of your work and contemporary developments in practice and the current status of the profession, what would you teach if you were now to run a studio? I am thinking of your quote a decade or so ago in El Croquis, when you had just been an external examiner at the AA [the Architectural Association School of Architecture] and noted that “designing internet sites is no alternative to the simple and irrefutable presence of buildings.”

PW: The designing of websites, blogs and so on was much hyped at that time under the rubric of “alternative practice.” The term embodies a profound and imbedded mistrust of conventional practice, with all its project controllers and procurement procedures.

GR: When you spoke at Parallax in 2009, you gave an impassioned talk about the consequences and opportunities afforded by the experimental culture of the AA in the period you were teaching there.

PW: When we entered the laboratory of the 1970s AA, experimentation was the exception, to be measured against the background of a stodgy and tradition-bound profession. The success and almost universal imitation of the AA’s “hothouse of creativity” teaching model has now almost incapacitated most schools in their role of providing the training necessary for the husbanding of ideas on their complex path to materialization. The creative academy is now the universal convention; a genuine avant-garde would by definition be the exception, an anomaly. While genuine creativity should be supported, institutionalized, imitative creativity needs to be questioned.

In my opinion what is necessary is a wider cultural re-validation, a new mythology of the physical, the material. If we were to be evangelical about the magic of our profession (one of the few that still conjures with the actuality of mass, material, place and atmosphere as well as representational currency), we would teach our students to recognize and value these qualities. I am thinking here of Robin Boyd’s crusade for modernism in the popular press. He also, by the way, filled my head (as a naive intern in his office, circa 1970) with intoxicating elsewheres of Japan and AA.

Source

People

Published online: 18 Dec 2013

Words:

Gerard Reinmuth

Images:

Christian Richters,

Thomas Rabsch

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2013