As a young graduate I shared the top half of an old, inner-city villa whose virtues included a clawfoot bath that looked north-east through a pair of narrow French doors onto a garden of mature chestnuts and oaks and, beyond, to the sea. The great pleasure of my morning was to lounge in the warm water like some yolky Bonnard, watching the sunlight tangle with drifting steam, contemplating the day to come. Now, of course, that house in Sydney is long gone. I have a chopping board made from its rafters, but the villa, the gardens, and most similar dwellings in cities like Sydney, have been obliterated by apartments and houses that are not even bath-capable. As if to complete the erasure, the word “bathroom” itself no longer carries any suggestion of bathing. (Apparently, going to the bathroom now means visiting the toilet.)

Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947), The Large Bath, Nude (1937–39), oil on canvas.

Image: Pierre Bonnard

What does it imply, this disappearance of the humble bathtub from our lexicon? Is it about space standards? Time pressures? Money? Or is something else going on?

I think it’s something else. For one thing, the shower, replacing the tub, has doubled or tripled in size, often occupying the full width of the bathroom, with a footprint at least the size of a bathtub. Plus, most dwellings now have two or three bathrooms where once there was one. So space is not the issue. Not money either, since three lots of plumbing is clearly at least as expensive as one. Nor is the tub itself the only loss. Even when there are multiple bathrooms, they are all – with very few exceptions – windowless caves buried deep within the dwelling, mechanically ventilated and artificially lit. This bespeaks a change not just of technology but of attitude.

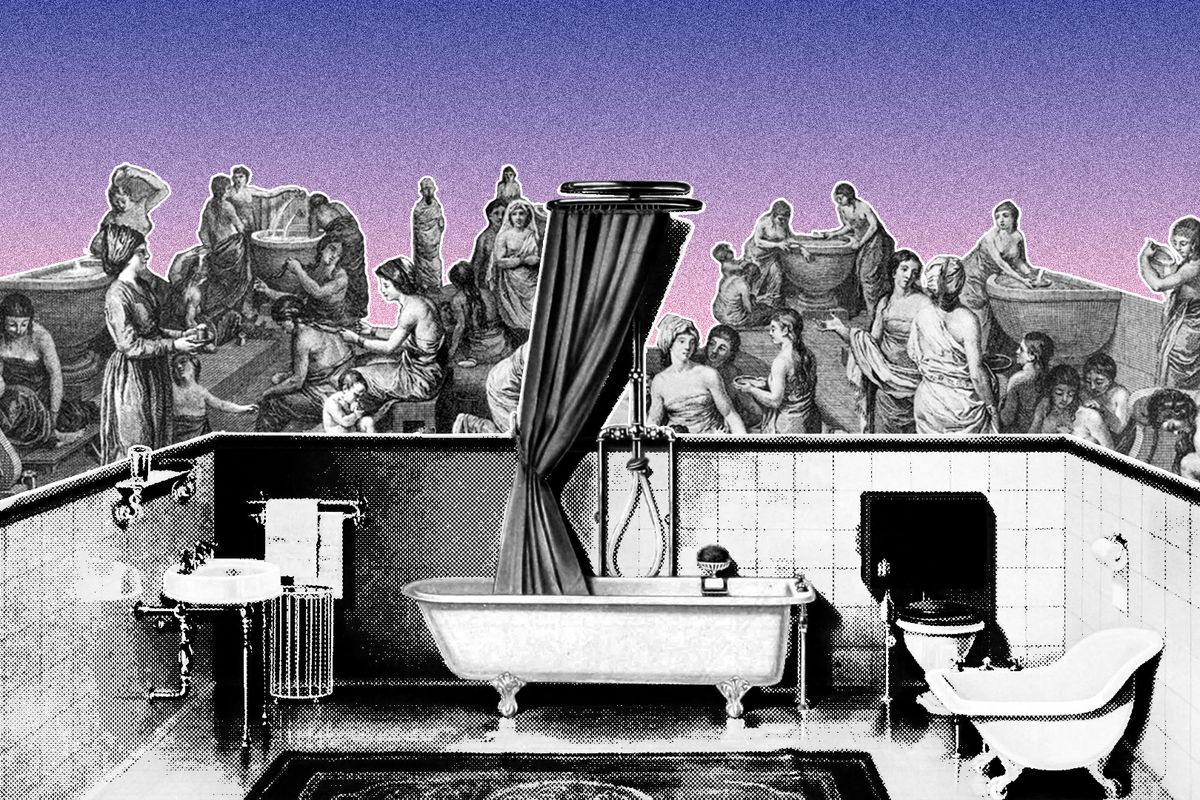

For millennia, bathing has been associated with ritual, and celebrated as a process of healing and purification, both physical and spiritual. The oldest known bath is the 5,000-year-old Great Bath of Mohenjo-Daro in the Indus Valley (now Pakistan). Said to have been part of priestly training, the mud-brick bath measured 12 by 7 metres, was more than 2 metres deep, and was sealed with bitumen.

The Ancient Greeks were well versed in the healing powers of sulphurous thermal springs, especially regarding skin complaints and joint pain. This was, in part, why baths were usually associated with gymnasia and fitness centres – an idea that the Ancient Romans took to its apotheosis by building magnificent edifices whose grand pools of different temperatures were fed by aqueducts and serviced by complex hot-and-cold ducting systems. But bathing wasn’t just about physical health; it was part of the principle of wellness. Encompassing mental, physical and spiritual wellness, this holistic take on sociocultural identity – augmented by shops, gardens, temples and libraries – was underpinned by the idea of the citizen.

Other cultures, too, celebrated the rituals of the bath. From the seventh century, the Hellenistic and Byzantine bathhouse, by then ubiquitous across the empire, was gradually adapted into the Turkish hammam, in line with the Islamic tradition of washing before prayer. The Jewish mikvah, not dissimilarly, requires the total immersion of women before marriage and after menstruation – a practice that seems to predate the New Testament (although Christian baptism also often requires immersion). Shinto, certain branches of Buddhism, and Balinese Hinduism also include ritualised immersive purification. Water, the universal cleansing medium, symbolises the crossing of a threshold into another state.

These days, in western culture, the ice bath is more fashionable than the thermal bath. Every day spa, health club, wellness retreat and, increasingly, neighbourhood gym now sports this substitute for the frozen lake of Nordic sauna tradition. Shinto has a similar tradition of cold-water immersion (misogi). But where misogi is valued as a spiritual purifier and link with the divine, our take on it – as betrayed by the term CWI (cold-water immersion) – is more mechanistic, justified by a raft of functional rationales and measures that relate not to the spirit but to physical wellbeing. The ice bath, we say – although the science on this is limited – reduces inflammation, boosts immune function, improves circulation, invigorates mood and enhances sleep.

Just as our instrumentalist and materialist culture has us justify whatever is merely beautiful (art galleries, say) or ethical (public housing) in terms of dollar yield, we reduce the benefits of the ice bath to numbers: cardio fitness, bpm, longevity, number of immersion minutes per week.

What is the cost of this reductivism?

Already, we have lost almost all ritual from daily life. Sure, there are pleasurable habits: the morning coffee, the evening dog-walk. But ritual implies a recognition of something larger than the self, an obeisance. Bathing was, in many ways, a last remnant of this. The internalisation of the bathroom and our quiescent acceptance of this – in our cleansing, why on earth would we need any connection with nature? – renders this demise permanent.

The fallacy comes from a lack of self-knowledge. It’s as though, a hundred years on, we have assumed the Corbusian worldview, in which human beings are largely mechanical creatures with material needs for food, shelter, money and efficiency, but no particular numinous qualities. So, a quick shower in a dark cave is every bit as good as a gentle soak in dappled morning sunlight.

Of course this is a lie, and one that goes to the heart of the design professions. Virtually all dwellings are now built by developers, with architects docilely doing their bidding. With no thought for the beauty and graciousness offered by an opening bathroom window, bedrooms and living rooms are aligned along the outside wall, and ablutions are buried in some airless hole behind the kitchen.

A recent paper in Australian Geographer by Hyungmo Yang, Hazel Easthope and Philip Oldfield makes this point. Entitled “Understanding the layout of apartments in Sydney: are we meeting the needs of developers rather than residents?”, it compares what people want with what developers (and their architects) provide – and it finds apartments wanting. Even then, the total internalisation of the bathroom, and the sensory deprivation that goes with it, is taken entirely for granted. The planning department’s Apartment Design Guide allows it, so the internalised bathroom becomes the default.

It needn’t be this way. Until 1997, for example, building regulations in Hong Kong required bathrooms to have external windows. Even 60-storey towers were designed this way, establishing a design custom that had the added advantage of articulating the facade. Since then, in Hong Kong as elsewhere, mechanical means have replaced natural methods. But there is no inherent reason why our architecture should not return the possibility of meaning, graciousness and delight to our daily ablutions. It is surely architecture’s core purpose, after all, to celebrate and enrich our relationship with nature.