Dana Cuff is a professor at UCLA Architecture and Urban Design whose work focuses on affordable housing and the politics of space. She is the founder of City Lab, a research centre within the university that uses design thinking to create better urban futures for Los Angeles. City Lab has presented at the 2010 Venice Architecture Biennale. Cuff is also the author of numerous books, including her most recent, Architectures of Spatial Justice. Cuff will be a keynote speaker at the upcoming 2024 Australian Architecture Conference. Ahead of her appearance, she sat down with ArchitectureAU to discuss the changing role of architects in society and how the profession can regain their agency in making the world a better place.

ArchitectureAU: You describe your work as a kind of intersection between spatial justice, cultural studies and architecture. Can you expand on what that means and what you do day to day?

Dana Cuff: I have a PhD in architecture and so I teach history, theory and cultural studies within architecture. I also write books about that, and I run a design research centre called City Lab, which tries to lay out a new model for practice that takes social justice, or spatial justice in particular, as the heart of a kind of architectural practice. That’s what my most recent book was about.

I very much come from architectural training where form and aesthetics are central to what we’re doing, and design is the mechanism by which architects demonstrate what they can contribute to the life of the city in our everyday lives. For me, one of the problems has been that [architecture] has been imagined as separate from social purpose. Like if you do one, you’re sacrificing the other. That’s a false dichotomy, in my opinion, but it’s one that persists.

The second part is that the form and aesthetics at the core of what we do has been reserved for privilege for the most part, except for in big public institutional buildings.

We haven’t democratised our capacity to make the world a better place. Those two things together mobilize the kind of work that I’ve been doing for the past 30 years.

AAU: When you talk about spatial justice, what exactly do you mean there?

DC: It starts with the work of some geographers who say that justice has a geography. We all know that in cities that there are certain parts of the city where you’re much more likely to have environmental problems; where your education isn’t going to be as good; where there’s not enough shade; where your infrastructure is more deteriorated and abandoned. These [areas] can be mapped.

So architecture has a means to encourage and advance social justice. You can think of that spatially. We see that in cities, but you can also see it in buildings that have a welcoming facade or ones that are closed off, ones that feel like they’re open to a general public and ones that feel more exclusive. We can think about the design of buildings and their context in ways that advance justice. [Justice is] not just something that we figure out in court or in our moral structure or in our ethics. It’s spatial.

AAU: How much of that do you think is a result of economic forces, or forces outside of architecture?

DC: That’s the most common question or argument and it’s ironic to me that it’s one that architects offer.

[Take for instance] the homelessness problem. Architects will say, that’s an economic problem or it’s a substance abuse problem or it’s a mental health problem and it’s not really an architectural problem. But of course, as architects, we can’t work in those other domains. It renders us powerless in that in the face of this issue.

But that work has our name on it. Homelessness. We’re the people who make homes.

It’s a contradiction to always say it’s somewhere else because the person who runs the economics program will say, it’s really substance abuse, and the substance abuse people will say it’s because of the prison system and everyone points somewhere else.

The only way that any solution will happen is if each of those parties who has some role in it, no matter how small it seems starts to do the work. It’s just labour and courage that are required to start making a difference.

We advance the situation in a way that’s aiming towards the world we want to live in instead of the world we’ve got.

And if we think that the only thing we’re capable of as architects is waiting for commissions from wealthy clients, you know, that that’s a powerless position to be in really?

AAU: What should architects be doing then?

DC: Yes, to regain their agency and to use their skills and expertise to follow their convictions, right?

I think all architects are interested in this, they really just don’t know how to do it.

I would just start by saying I’m not trying to transform the parts of the profession that are already working well. If someone’s designing better schools and museums thoughtfully, they’re already making the world a better place.

But when we find that our role needs to change, say in the condition of affordable housing, most architects will say the regulations and the financial tools are so strict, that’s why we get the same solution all the time.

In my mind, that’s not an adequate response because we get a lot better housing in some cases than others. There’s really good affordable housing, and then there’s pretty conventional affordable housing. So someone’s got it figured out and we need to understand how and why.

If we can see that there are contextual barriers that are preventing us from doing the kind of work that we want to do in the world, we need to work against those barriers.

For instance, we have a big problem with Not in My Backyard (NIMBY) neighbourhood politics, which has really prevented us from being more equitable in the way we provide architecture and housing in communities.

What we do at City Lab and what other [research] centres are doing is trying to solve that through design at a bigger level.

We’ve written state policy that makes it possible. We rezoned state school land for housing because our teachers couldn’t afford to live in the districts where they taught and our janitors were living in their cars outside the schools. We could then work to see what kind of design solutions might work, and where on school land, and then work with legislators to change the regulations.

Education Workforce Housing, City Lab research into the potential for land owned by school districts to be used to house teachers and other employees, which led to legislation co-authored by City Lab to facilitate the development of affordable and mixed income housing for teachers and staff.

Image: City Lab

It means expanding our ideas about what the architect’s job is, but it’s also using the architect’s key skills to expand those ideas.

The other thing we can do is create demonstration projects, or prototypes, to do a project where we understand it as a model, not a solution, but as a model for what should be happening next.

AAU: Can you talk us through how that whole process worked from say an initial hypothesis where you wanted to test out the research, the demonstration project, to then making legislative changes?

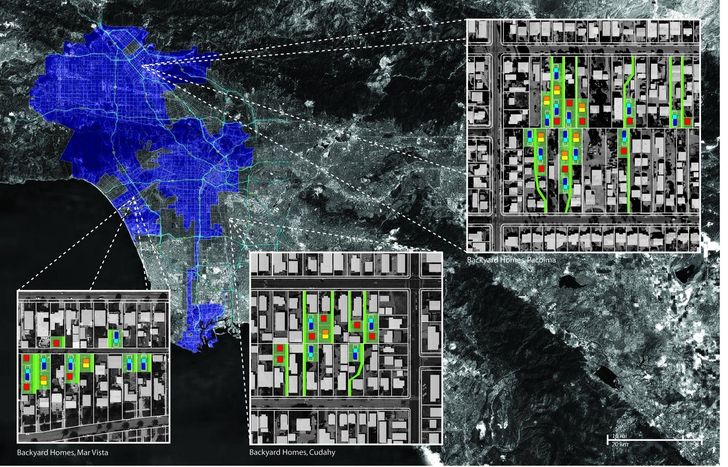

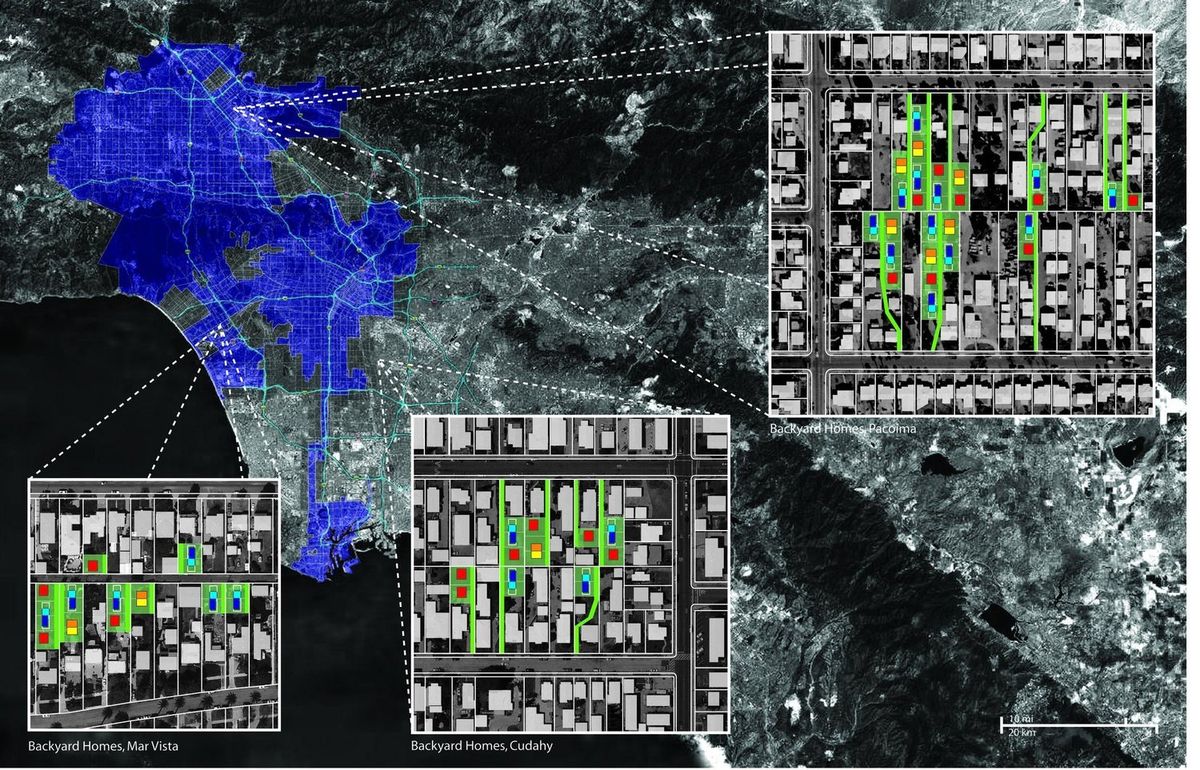

DC: The most exemplary case that I could describe would be our Accessory Dwelling Unit, or backyard homes, research, design and law.

When we were looking in California at forms of affordable housing that were happening in the city, particularly in low income neighbourhoods and especially in low income neighbourhoods of colour, people were building granny flats on their own, informally, or in other words, illegally, and it was working. It meant that they could get two houses on their site, sometimes three, sometimes more. The grandparents could live there, there were affordable solutions for their kids who were coming home from college because they couldn’t get a job right away.

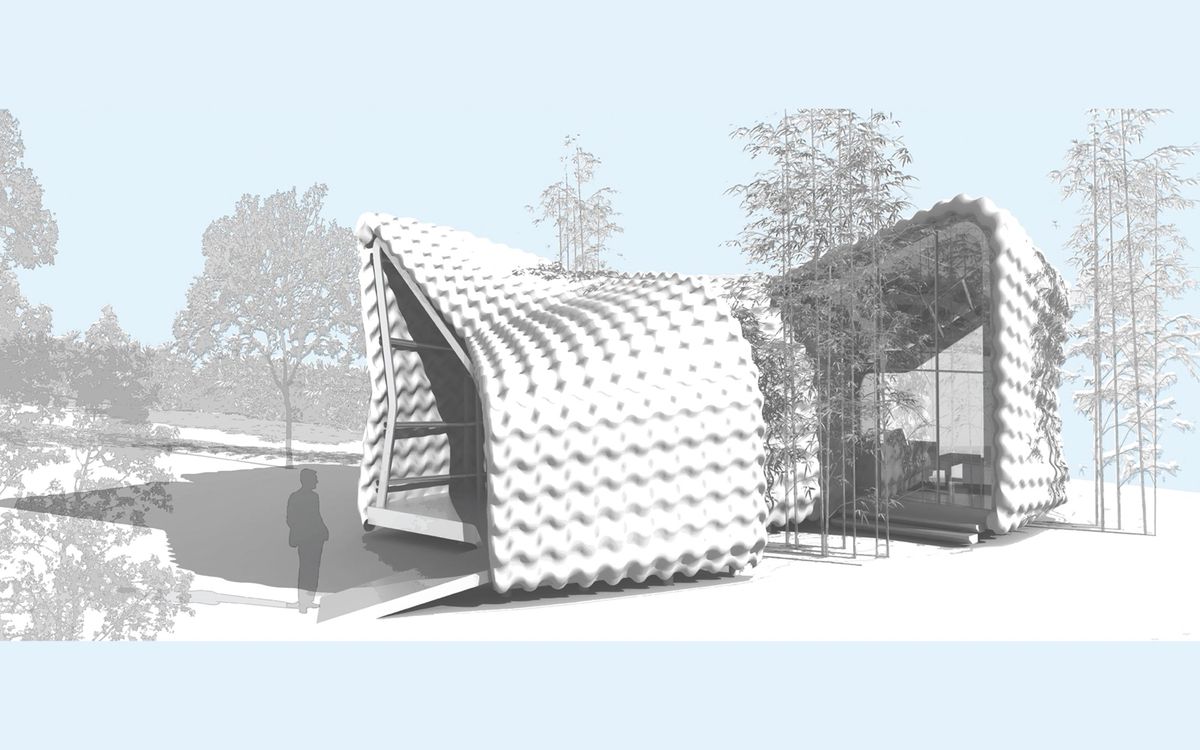

So we started trying to see if there would be a kind of architectural prototype, a module or a prefab model – that’s kind of the way all architects think – that we could produce or encourage or set up a design competition for, which could be easily placed in different backyards. That was the beginning of about 10 years of research in the end. But as it turns out, backyards are like thumbprints, every one is unique and thinking that there might be a single fit was not a productive direction for us.

We started studying different types of lots. We discovered that corner lots, alley lots and large lots were ones that could really be amenable to granny flats. You can see how we were progressing to get a better and better understanding.

City Lab’s Backyard Homes research, which led to legislation co-authored by City Lab to encourage homeowners to build granny flats.

Image: City Lab

Then we started trying get people to take the barriers away. There were lots of barriers that prevented people from building backyard homes. Some strange laws existed: certain kinds of zoning, certain alley conditions. We found there were five or six key issues that prevented anyone from using the very small legal window.

So then we built a demonstration house that you could carry down the side yard build with unskilled labour. It got a lot of press, which was very effective. Getting the word out was key because, you can get isolated when you’re doing research on a university campus about something as wonky as architecture and law.

This little demonstration went public and in the end that brought the attention of lawmakers. We ended up writing a very effective law because we knew all the design limits as well as the financial problems, and the lending problems and the zoning problems. But knowing all of that together meant that we could write good legislation that’s really produced tens of thousands of housing units now.

AAU: how did you convince the legislators to take on this kind of reform, particularly in the face of NIMBY politics?

DC: Well, we couldn’t do it at a local level. There were always a few very powerful, loud voices that didn’t want change. So, we jumped to the equivalent of the provincial level, where there was a much broader understanding of the housing crisis without local pressure. We had to convince them still, but we had enough data behind us.

I remember at one point I had to go before all these different committees that had to move it through the government structures. One of the legislators said to me, well, you know, this won’t apply in our community. And I said, I have the data for your county and I can tell you that there are this many sites and this many people who already have granny flats that are illegal. And she said, we’ve never had data before when we passed legislation.

I still believe that, to a large extent, it was the credibility of our evidence that we gathered through designs, research that made it possible to pass pretty radical legislation that changed the zoning of the entire state from the family homes to duplexes and now it’s changed again really wonderfully to three-plexes and four-plexes.

Tens of thousands of units have been built, just because that law passed. And they were not built with any subsidies. It sparked bottom-up production of housing.

AAU: It sounds like to me that your process to identify the barrier and research all the ways to kind of get over that barrier and then do a demonstration project?

DC: Yes, I think that’s a good summary of it. The first thing you have to do is find an issue where architects can leverage design to help solve it. That’s the starting point. If I were a different person, I could do the same work with sustainability issues for instance. I think everyone has mechanisms in their own forms of practice to do the work that follows their convictions, whether they’re about sustainability or about affordability, or public space, for example.

Dana Cuff will be a keynote speaker at the 2024 Australian Architecture Conference, to be held in Melbourne from 8 to 11 May. See the full program and purchase tickets on the Australian Institute of Architects website.